Sentences and Socks: Mixing and Matching

In the past few years, I have noticed a phenomenon sweeping

the pre-teen female population: mismatched socks. I must admit that I am a bit

disappointed to have missed out on this fad—I love fun socks! Yet there is

still something to be said for order in the chaos. While mismatched socks are

fun for a while, there is still something satisfying to me about matching up my

socks together when they come out of the laundry.

I feel the same way about parts of sentences. Allow me to

explain.

Whether we realize it or not, our speaking and our writing follow certain patterns. For example, in the English language, simple sentences usually have a subject (who or what the sentence is about), a verb (action word), and then an object (the word or phrase receiving the action). Thus we end up with a sentence like this: He threw the ball. Sentences such as Threw he the ball do not sound right, nor does The ball threw he. These sentence patterns may be used in other languages, but they do not exist in English.

There are some sequences of matching patterns that are tricky

to differentiate. While there are multiple ways that sentences can be

mismatched, this post will cover one of the most commonly mismatched combinations

of two different sentence patterns.

Mixed Construction

If someone sneezes, many people respond with “bless you” or

“gesundheit.” When someone sneezes,

people are expected to respond; it is, to some extent, the expected pattern of

behavior. Sentences work in a similar way. When you have certain beginning of a

sentence, a specific and aligning ending is expected.

Example of mixed sentence

construction: By providing students

with more engaging curriculum will motivate students to participate in

class.

The problem here is that the underlined phrase is being

pulled in two different directions because there are two parts of two patterns,

and they do not work together.

Pattern 1:

Usually, sentences that begin with the word by have a certain pattern, like this: By running fast, I won

the race.

Notice the pattern. First you have a descriptive phrase,

explaining how something happened (by

running fast), and next you have the complete sentence that this phrase is

modifying or describing. In the example above, the

complete sentence after the descriptive phase is a simple one, made up of a

subject (I), verb (won), and object (the race). Another

grammar term to note is predicate, which

means the words or phrases that come after the subject to convey information

about that subject.

So any time a sentence starts with by, this is the pattern to follow:

[Descriptive phrase +

Comma] + [Subject +

Predicate]

All these sentences are examples of a correct way to use

this by phrase:

By keeping low to the ground, he was able to escape the fire.

By slowing her pace, she was able to run farther.

By being a good student, he was accepted into the University of Minnesota.

Here is another way to look at this type of sentence:

Here is another way to look at this type of sentence:

[By] + [-ing word + phrase] + [comma] + [independent clause (complete sentence)]

Example: By completing the project, the researchers discovered how to best address the problem.

View the pattern and the sentence in this table to see how they align:

| [By] | [-ing word + the rest of the connected phrase] | [comma] | [independent clause (complete sentence)] |

| Completing the project | allowed the researchers to discover how to best address the problem. |

,

| the researchers discovered how to best address the problem. |

Let’s take another look at the

original mixed construction sentence:

By providing students with more engaging

curriculum will motivate students to participate in class.

Now, you can see that the

sentence does not follow this pattern. The –ing

word and the rest of the phrase should work with only by in this sentence. Instead, that phrase is trying to function in

another way, and the sentence starts to go into another pattern.

Pattern 2:

This next pattern begins with –ing words. Instead of using those –ing words to describe the subject, this pattern actually uses

those –ing words as the subject of the sentence. Here’s

an example: Knowing how to cook is

important for everyone.

What is important for everyone? Knowing how to cook. This is your subject. See how this phrase can

work as a subject, and the rest of the sentence works as the predicate? Notice how the verb (is) comes directly after the full subject, so this is the pattern

that this kind of sentence follows:

[-ing word

(This is the subject of the sentence)] + [no comma] + Verb + Predicate

Here are a few other

examples where the –ing word and

phrase work as the subject of the sentence:

Brushing your teeth is something you should do twice a day.

Running was his favorite hobby.

Playing the saxophone makes me happy.

Here is another way to break it down:

[-ing word + phrase] + [predicate (verb and object, etc.)]

Example: Completing the project allowed the researchers to discover how to best address the problem.

[-ing word + phrase] + [predicate (verb and object, etc.)]

Example: Completing the project allowed the researchers to discover how to best address the problem.

Here's another way to view this pattern and the sentence

in this table to see how they align:

| [-ing word + the rest of the connected phrase] | [predicate (verb and object, etc.)] |

| Completing the project | allowed the researchers to discover how to best address the problem. |

To allow your readers to best understand your ideas,

remember to consider and then follow these required sentence patterns as well

as others. As you proofread, look at your sentences carefully. Ask yourself, Does this part of the sentence have a pattern

that requires a corresponding part? Go ahead and mismatch your socks, but

if you want to communicate clearly, remember to avoid mismatching sentence

patterns.

.png)

Rachel Grammer is a writing instructor and the coordinator of student messaging at the Writing Center. A self-professed grammar nerd, she loves discovering the social interests of Walden students and hearing the stories that shine through their writing.

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

The Easiest Way to Avoid Plagiarism

As you

can tell from this post’s title, this week, I want to share with you the easiest

way to avoid plagiarism in your writing. Here it is:

WriteCast Episode 11: "Doesn’t Meet Requirements"—Strategies for Following Your Assignment Instructions

This month, Nik and Brittany talk about strategies for understanding and following your assignment instructions.So, you may have had this experience...where you feel really, really strong about something that you turn in into your course. You've spent a lot of time on this assignment, you've put a lot of effort into it, and you're probably feeling really proud of it. And then you get it back with your instructor's comments on it, and you find that you've lost points because your instructor says that the paper doesn't meet the requirements or follow the assignment instructions. Now, if you've ever had an experience like that, I think you'll find this episode really helpful. - Host Brittany

To download the episode to your computer, press the share button on the player above, then press the download button. Visit the Writing Center's WriteCast page for our episode archive and transcripts. Happy listening!

WriteCast is hosted by writing instructors Nikolas Nadeau and Brittany Kallman Arneson and produced by writing instructor Anne Shiell. Check out the podcast archive for more episodes.

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

Dissertation and Scholarly Research: Simon and Goes Provide Recipes for Success (Book Review)

If you are writing a dissertation, doctoral or project

study, or any other doctoral-level capstone research project, chances are it is

the first time you have done anything of the kind. While you have years of

practice with what it means to participate in the classroom, complete

proscribed assignments, and even conduct original research, the doctoral

capstone research project is a unique document and a unique task. Why not take

advantage of any number of excellent resources available for helping you

through the various steps and stages of tackling a project of this size?

|

| Image (c) www.dissertationrecipes.com |

Authors Marilyn K. Simon and Jim Goes have done just that, and

they just happen to be Walden faculty to boot. In their resource, Dissertation and Scholarly Research: Recipes for Success—A Practical Guide to Start and Complete Your Dissertation, Thesis,or Formal Research Project, Simon and Goes (2013) have crafted a guidebook

that addresses students working outside of traditional brick-and-mortar

institutions to complete their degrees. Their use of metaphor (specifically,

food) helps make what could otherwise seem like a dense and complex process

more, well, digestible.

The mnemonic devices, “cutting board” exercises, and links

to outside resources offer practical and accessible advice, and the guide

offers help with everything from how to formulate your research questions to

what to do when it comes time to format your document for final submission to

ProQuest.

While you could certainly sit down and read this book cover to

cover, one of the guide’s strengths is in offering a breadth and specificity of

information, so you could just refer to the table of contents and read those

sections that pertain to your current needs.

One thing that can be frustrating at times when conducting

this level of research in a virtual space is how to know where to go for the

right information and how to get a hold of who can answer your questions. This

guidebook is particularly relevant to Walden student needs in this regard

because it addresses content and design as well as APA and scholarly style. Simon

and Goes did a particularly thorough job really explaining to the reader how

everything fits together and how the way you craft and express an idea can support and inform your research.

As with any comprehensive guide, the sheer amount of

information can seem daunting at first, but everything is organized and

presented in such a way that a reader will not feel overloaded. Dissertation and Scholarly Research: Recipes

for Success should be high on the list of any Walden student looking

for that extra bit of guidance and support while beginning this next step as a

scholar-practitioner.

.png)

Lydia Lunning is a dissertation editor and the coordinator for Capstone Resources in the Writing Center. Lydia also helps oversee the Walden Capstone Writing Community, a place where doctoral students working on their proposals and final studies can connect with colleagues and get support through the capstone writing process. Outside of Walden, Lydia enjoys literature for children and young adults, writing pedagogy, contemporary cinema, and cooking.

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

Defining a Gap in the Literature: On Proving the Presence of an Absence

It’s standard in any study to point out the gap in the

literature you're seeking to fill. (Else why do the study—unless it’s a

replication study?) Like the hole in the donut, the gap is defined by what surrounds

it. Yet it’s common to read statements in the literature review such as (a) “I could

not find anything on [the issue] in the literature” or (b) “Very few studies,

if any, talked about [the issue].”

It’s not easy to prove a negative: This does not exist. Therefore, to define a gap, a precise and

exhaustive search is needed to identify all the studies around—but not

touching—your topic. Reporting what you did find, what is known (the donut) implies

what is not known (the hole in the

donut). The unknown is the gap, your topic.

The problem with (b) is that it leaves readers wondering

about what you know; it asks them to just accept your claim with no support. If

your search were thorough, you would know whether any or just a few studies

talked about your issue. If there were none, then, just as in (a), you’d define

the gap by identifying the studies around—but not touching—your precise topic. The

number of studies required to make that point could vary. However, if there

were some studies, then you'd need to

discuss only those studies in order to confirm for your readers that something was

indeed missing—your angle on the

issue.

If your search was precise—if you named all the databases you used (not just the names of portals, such as ProQuest or EBSCO), if you listed all the keywords (not phrases) you used, and if you specified your time range—then your committee (and future readers) could have confidence that you were in the right ballpark. If you then described what was known—using a broad set of studies or a handful of specific studies—then your readers could have confidence in your claim because they could see your process, and judge the data adduced, to “prove” a negative and reveal the presence of an absence.

If your search was precise—if you named all the databases you used (not just the names of portals, such as ProQuest or EBSCO), if you listed all the keywords (not phrases) you used, and if you specified your time range—then your committee (and future readers) could have confidence that you were in the right ballpark. If you then described what was known—using a broad set of studies or a handful of specific studies—then your readers could have confidence in your claim because they could see your process, and judge the data adduced, to “prove” a negative and reveal the presence of an absence.

.png)

Tim McIndoo, who has been a dissertation editor since 2007, has more than 30 years of editorial experience in the fields of medicine, science and technology, fiction, and education.

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

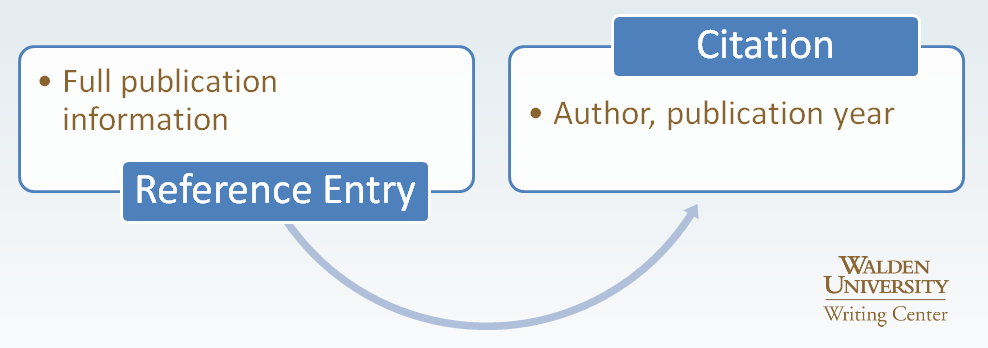

A Match Made in Heaven: Reference Entries and Citations in APA

To me, knowing how and why rules apply to me always makes them

more relevant and makes me more inclined to learn and use them. This approach makes sense when talking about APA Style because APA rules can seem so

arbitrary. So, with the approach of helping students understand the reasoning

behind the APA rules, let’s start at the beginning: the reference list.

What is a reference list?

The

reference list is the foundation for citing sources in APA. In APA, writers

include all sources they use within the body of the paper, but only those sources, in the reference

list. This is a little different from a works cited or bibliography (lists of

sources used in other citation styles, like MLA and Chicago),

which sometimes include sources the author consulted but did not end up using

in the paper.

In APA, if you cite a source anywhere within the paragraphs

of the paper, it should also appear in the reference list. Similarly, only

sources used within the body of the paper are included in the reference list.

It’s always a good idea to proof for this relationship before finishing your

paper. If you take just one thing away from this post, remember this: Every source cited in your paper must have an entry in the reference

list, and your reference list should not contain any sources that you didn’t

cite in your paper. This rule applies for almost

every source you cite in-text. The only exception to this rule is personal communication citations, which do not have corresponding entries in the reference list.

What is its purpose?

The reason you need to list all of the sources you cite in the body of your paper in the reference list is so the reader can trace the information you used to inform your writing. Imagine that you incorporate a statistic regarding high school graduation rates in your paper; you include a citation to your source in the sentence that uses the statistic. The reader could then use that citation to find that source and its full publication information in your reference list, allowing the reader to find the source itself.

This function of the reference list is also why citations

are structured the way they are. Because sources are listed alphabetically by

author in the reference list, citations include the author(s) of a source and

the source’s publication year.

How do you create reference entries?

Because the purpose of the reference list is to help

the reader track the sources you used, a reference entry must include enough

information for the reader to find the original source. This includes the

following basic information:

- Author(s) of the source

- Publication year of the source

- Title of the source

- Publication information of the source

Check out these great resources to help you create reference entries:

- Common Reference List Examples page on our website

- Recordings of the APA Citations webinar series

- APA Style Blog

And, of course, if you ever get stuck creating a reference

entry, simply let us know via e-mail at writingsupport@waldenu.edu.

Now that you know the reasoning behind a reference list and

how it relates to the in-text citations in your writing, I hope you’ll have a

better understanding of why the

reference list is so important.

.png)

Beth Oyler is a Writing Instructor and the Webinar Coordinator for the Writing Center. She lives in Minneapolis and recently graduated with her MA in English.

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

2 comments :

Post a Comment