Misplacing the Word 'Effectively'

In English, the position of a word in a sentence is significant.

Where a word appears in a sentence

depends on whether you are writing about time, a question, an adverb; it

depends on whether you are writing a positive sentence, a negative sentence, or

a subordinate clause.

Adverbs are problematic because they can appear before the subject of the sentence, between the subject and the verb, or after the verb. Their meaning will

generally change according to position in the sentence. So it’s not uncommon to

see adverbs misplaced in written English.

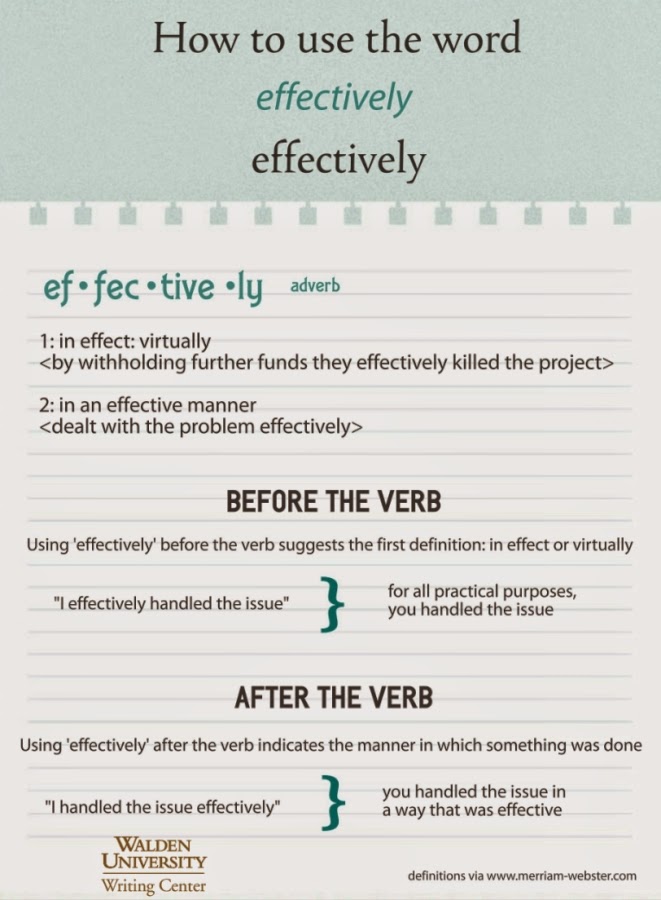

Such an adverb is effectively.

According to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary (preferred by APA and

Walden), when placed between the

subject and the verb, it means in effect or virtually <by

withholding funds they effectively

killed the project>. But when it is placed after the verb, it means in

an effective manner <dealt with the problem effectively>. Follow this URL: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/effectively

Putting an adverb in the wrong position in a sentence will likely

confuse readers. For example, you would not want to write, “by withholding

funds, they killed the project effectively,”

if you meant to say only that the project was virtually killed (“by withholding funds, they effectively killed the project”).

To say how something was done, the adverb must be used after a verb. Use this infographic below as a handy reminder:

Practice: Do a search (hint: use CTRL + F) in a piece of your writing for the word 'effectively'. Are you using it as you mean to? Share with us in the comments.

Tim McIndoo, who has been a dissertation editor since 2007, has more than 30 years of editorial experience in the field of medicine, science and technology, fiction, and education. When it comes to APA style, he says, "I don't write the rules; I just help users follow them."

| Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time |

Why I Almost Gave Up on My Degree Program and What Kept Me Going

Right now, I am in the unique position of being a staff

member in the Walden Writing Center as well as being a student in Walden’s EdD

program, and I am currently working on my proposal. I thought that because I

know a great deal about the resources that are available to students and

because I am well acquainted with the process and expectations of the doctoral

program, I would be able to fly through the program with ease and grace without

needing to rely on the numerous sources of support that Walden offers. Boy, was

I wrong.

I love being a student, and I was right on track with my

doctorate while I was in my courses. I was capable of going at it alone; I did

not rely on my instructors, peers, or other resources, such as the Writing Center’s

paper reviews or webinars, very much. I got into a rhythm, and I really enjoyed

the program. Then the coursework ended. Now, you are probably reading this and

thinking that maybe I have really poor time management skills, which would be

reasonable considering the lack of a structured timeline during the proposal

stage. Or you might think that I do not have the intellectual threshold or

writing skills I need to move forward in the program. None of those were the

problem, though. I am a planner by nature, so I like to think I have pretty

good time management skills. I know I have the writing skills (the intellectual

threshold part has yet to be determined), so these were not the problem. The

problem I had was life.

|

| Do you ever feel like giving up on a class or program? What keeps you going? Photo by Ryan McGuire of BellsDesign | CC0 |

I recently read an article

in The Chronicle of Higher Education* about

Ph.D. students and how difficult it is for them to get their doctoral degree in

a timely manner. The recurring theme I noticed in the article was unexpected

life events, and I have found that this rings true with me as well. I am willing

to bet that many of you can relate to me. I am a student in a doctoral program,

but I am also a full-time employee, a parent, and a person who has family, social,

and community obligations. I balance many things in my life, and I plan,

schedule, and make lists to help make it all happen. When it all flows like I

expect it to, it is great. However, life has a habit of surprising us, and planning

feels so futile to me at times.

The life event that derailed me from making progress on my proposal was the death of my mother-in-law. She became ill, was hospitalized, and then became comatose and finally passed away over the course of a few weeks. I stepped away from my proposal in order to make time for my family because they needed me. I did not just take time off for the funeral, though. My mother-in-law’s death had residual effects on my husband, my children, and my in-laws. I ended up taking a few months off, and the longer I was away from my proposal, the more resistant I became to returning to it.

The life event that derailed me from making progress on my proposal was the death of my mother-in-law. She became ill, was hospitalized, and then became comatose and finally passed away over the course of a few weeks. I stepped away from my proposal in order to make time for my family because they needed me. I did not just take time off for the funeral, though. My mother-in-law’s death had residual effects on my husband, my children, and my in-laws. I ended up taking a few months off, and the longer I was away from my proposal, the more resistant I became to returning to it.

It was really tough to make myself check my student e-mail

or even enter the Blackboard classroom because I felt so behind compared to my

peers in my cohort. I was constantly finding reasons to put off working on my

proposal, and I had almost resigned to let it languish indefinitely as I contemplated

quitting the program. I was really frustrated and disappointed in myself, but I

just could not get motivated or inspired to continue.

Then something wonderful happened. I opened my student e-mail. There was an e-mail from my chair, and another one from a student in my cohort. They wanted to know how I was doing, they offered help, and they sent encouraging words about how they believed in me. They reminded me of how far I have come, and they gently coaxed me back into the classroom. Gradually, my academic spirit and my motivation returned as they continued to support me and persuade me to keep going.

Then something wonderful happened. I opened my student e-mail. There was an e-mail from my chair, and another one from a student in my cohort. They wanted to know how I was doing, they offered help, and they sent encouraging words about how they believed in me. They reminded me of how far I have come, and they gently coaxed me back into the classroom. Gradually, my academic spirit and my motivation returned as they continued to support me and persuade me to keep going.

Find strength in the relationships you build, and lean on

folks when you need to do so. In turn, support others.

What I hope you can take away is this: life happens. It is

messy and it gets in the way. When it does, look for support within your Walden

community. Find strength in the relationships you build and lean on folks when

you need to do so. In turn, support others. If you notice one of your

classmates is not as active in discussion boards or seems to be falling behind,

reach out to him or her. You have no idea what other students might be going

through, and you never know how much a kind word or a show of support can mean

to someone. It made such a difference for me.

Do you need help finding a writing community? Join a January writing group or the Walden Capstone Writing Community.

* Walden students: Access the full text of “The Ph.D.

Student’s Ticking Clock” through

the Walden library.

.png)

Amy Kubista is the Manager of Writing Instruction at the Walden Writing Center. She is pursuing an EdD with a specialization in higher education and adult learning.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

WriteCast Episode 16: Why You Need to Join a Writing Community

Being a part of a writing community is a great way for student writers to connect with each other, stay motivated, keep each other accountable to writing goals, share challenges, and celebrate successes. This month, Nik and Brittany chat with Dissertation Editor Lydia about the importance of having a writing community, the communities that the Writing Center offers, and new resources for doctoral students.To download the episode to your computer, press the share button on the player above, then press the download button. Visit the Writing Center's WriteCast page for our episode archive and transcripts. Happy listening!

Next year, we're going to be trying another kind of writing community: small, private writing groups through Google+. Fill out this brief survey to become part of a group for January!

Resources mentioned in this episode:

Walden Capstone Writing Community

Writing Center on Facebook

Writing Center on Twitter

"Writing Together: How Peer Writing Communities Can Be Your Secret to Success" blog post

WriteCast is hosted by writing instructors Nikolas Nadeau and Brittany Kallman Arneson and produced by writing instructor Anne Shiell. Check out the podcast archive for more episodes.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Responding to Feedback is Hard--Here's Why You Should Do It Anyway

This fall, for the first time in my life, I was accused of

plagiarism. I had written a literature review for my online graduate program,

and due to the frequency of citations as well as the length of my reference

list, my draft received a rather high similarity score in Turnitin (TII).

Having felt proud of the work I submitted and confident in my paraphrasing and

citation skills, I was shocked and disheartened to see a note from my professor

advising me to rewrite the entire paper.

Okay, so this was not exactly an accusation, but it sure felt

like one! After a moment of panic, I wrote back to my professor, politely

pointing out that the only flagged content consisted of citations, references,

and a few common academic expressions. We engaged in a small debate on the

topic, and at last my professor concurred, acknowledged that a high similarity

was to be expected due to the nature of the assignment, and even thanked me for

reminding him of the need to analyze TII reports rather than judging a paper

solely on its similarity percentage. This story has a happy ending, but I found

the whole experience to be incredibly uncomfortable, and I had to wonder: If I

did not have so much professional experience with TII, would I have stood up

for my work? Would I have contacted my professor at all?

|

| Original image (c) 2014 Doug Robichaud via Life of Pix |

My purpose here is not to discuss how to interpret TII

reports—we’ve done that in previous posts—nor is it to criticize my professor, who only

wanted to help me improve my writing. Instead, my goal is to offer a student’s

perspective on Amber’s

recent blog post as well as to WriteCastEpisode 15, both of which focus on responding to faculty feedback. These

resources offer invaluable tips and best practices. However, as I learned this

fall, engaging with feedback can be harder than it sounds – even for someone

who reviews academic papers nearly every day.

Writing that first e-mail to my professor was not easy. I

had to rein in my initial reactions, including panic that I had inadvertently

plagiarized, indignation (“Don’t you know what I do for a living?”), and a

natural inclination to acquiesce to authority figures. I had to analyze an idea

that I found unpleasant—the possibility that I had plagiarized—and ask myself: Can

I see where my professor is coming from? Do I understand the nature of his

concern? Do I see anything that I did wrong? What evidence do I have to support

my perspective? And then, after all of this, I needed to craft an articulate,

respectful, convincing e-mail voicing my questions and concerns.

Engaging takes time. It takes mental effort. It requires us

to juggle confidence in our perspective with open-mindedness and humility. No

wonder so many of us, at the end of a long working day, are wary about

expending this kind of effort. No wonder we want our homework to be as simple

and painless as possible. And no wonder that even when we feel confused,

isolated, or frustrated, we hesitate to reach out, to challenge, to ask.

But this type of engagement is exactly what we signed up for

when we enrolled in higher education. If we are unwilling to engage our faculty

in conversations and to learn more about our work, we run the risk of become

passive consumers of knowledge or of falling into learning ruts. When we

actively communicate our questions, comments, and concerns, however, we are

co-creators of our learning experiences. We are holding up our end of the

academic conversations. From my perspective, this is our responsibility as

students: not just to absorb information, but to process that information,

interpret it, make it relevant, and contribute

to it.

So the next time you receive difficult feedback from a

professor, a classmate, or even a Writing Center writing instructor, remember the following:

1. You’re not alone! If you have a question or concern, odds are that someone else does as well.

2. Your instructors don’t know how to help you unless you contact them. They can’t meet your needs until you make those needs known.

3. It is your right and responsibility to construct your own learning experience. Make it a good one.

.png)

Kayla Skarbakka is a writing instructor and coordinator of international writing instruction and support. She is earning her M.S.Ed. from Purdue University.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

New in 2015: Join a Walden Writing Group!

We’ve

talked about the importance of having a writing community here and here on the

blog, and we'll also be talking about it in our next WriteCast episode (stay tuned!). We know that finding such a community can be challenging, though, particularly at an online institution. That’s why next year, we’re trying out a new service: small, private writing groups for Walden students.

The groups will run for four weeks in January and will take place in Google+ communities. A Writing Center staff member will organize the groups and will post some

discussion questions to get things started, but what you want to get out of the group will be up to you and your group

members. To help make the

groups useful for everyone, we just ask that you commit to checking in to the

group twice a week.

The writing groups are open to all Walden students--undergraduate and graduate--working on coursework. If you're interested in joining a writing group, please sign-up via this brief survey. If you're a doctoral student working on your proposal, we encourage you to form a group through the Walden Capstone Writing Community.

What

can you do in a writing group?

Discuss writing questions, challenges, and successes

Discuss writing questions, challenges, and successes

Motivate

each other

Keep

each other accountable to writing goals

Share

writing tips and advice

Get

feedback from peers on your writing

We're going to start forming groups this December, so fill out the sign-up survey today!

If you have questions about the groups, please ask them here in the comments.

.png)

Anne Shiell is a writing instructor and the coordinator of social media resources at the Walden Writing Center. Anne also produces WriteCast, the Writing Center's podcast.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

What's Your Writing Question?

If you're a Walden student (or a student somewhere else), I'm sure you have at least one writing question just waiting to be answered. Maybe you're wondering why you have to use APA style. Maybe you have trouble with writer's block and want suggestions for getting unstuck. Maybe you rock your introduction paragraphs but struggle with conclusions. Whatever it is, we can help!

We're gathering questions about writing to be asked and answered on a WriteCast podcast Q&A episode. Simply click below (alternatively, visit our voicemail page) to record your question using your computer. Here are a couple guidelines to ensure the best recording:

- Please ask your question slowly and clearly.

- If you have more than one question, please ask them separately.

- If you'd like, feel free to introduce yourself and your program or degree. You can also remain anonymous.

- If you have a microphone or headset with a mic, using it will provide the best sound quality. If you don't have a microphone, that's fine--just try to get close to your computer when speaking.

Note: If you're a Walden student or faculty member and you need an immediate answer to your question, also feel free to e-mail it to us at writingsupport@waldenu.edu.

Thank you!

WriteCast is hosted by writing instructors Nikolas Nadeau and Brittany Kallman Arneson and produced by writing instructor Anne Shiell. Check out the podcast archive for more episodes.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

What’s the Difference Between a Summary, a Transition, and a Preview in a Capstone Study?

(Note: For the sake of

simplicity, this blog uses the dissertation terms chapter and section. In doctoral studies, the

cognates are section and

subsection.)

At the end of all but the last chapter of a capstone (dissertation or doctoral study) study,

most rubrics require three elements: a summary

of the current chapter and a transition

statement to get readers from the current chapter to the next chapter. Then, at

the start of that next chapter, there is a preview

of its major sections. Because guidance from the various programs says little

about how these three elements differ, they tend to be treated as equivalent to

one another. For example, the summary may just list the topics covered in the

chapter (much like the Table of Contents does); the transition may just list the

next chapter’s main headings (much like the Table of Contents does); and like

the chapter summary, the preview at the start of the following chapter may just

list the next part of the Table of

Contents. Alas, such redundancy is not very helpful for readers. The goal of

this post is to suggest how to distinguish these elements in the narrative.

Think of Your Study as a Story

First, try to see your study—and write about it—as if it

were a story: There’s a beginning (Introduction, Literature Review), a middle (Methodology,

Results), and an end (Discussion, Conclusions, Recommendations). In the summary

of each chapter, recap the main points or essence of the chapter, but do it in

a way that gives your readers a sense of the study’s evolution. A mere list of

topics (what was covered), is not enough. Make sure it’s clear how all the

elements fit together--for example, the relationship among the problem,

purpose, and research question or guiding question. You’ll be writing from a narrow

perspective, that is, the current chapter.

After the chapter summary comes the transition statement, which forms a bridge between the current

chapter and the following chapter. A mere list of topics is not helpful; guidance

on the interrelationships is needed. Describe how the current chapter leads to the

following chapter and how the next chapter advances your story (study). Write

from a broad perspective, that is, your entire study.

While the transition statement serves to bridge chapters, the

chapter preview opens the following chapter.

In the preview, tell your readers what you will cover in just this chapter. Again,

be clear about how all the elements fit together. A list of topics is not

helpful. The goal is to make sure that your reader does not feel lost. Here,

again, you’ll be writing from a narrow perspective, that is, the current

chapter.

None of these three is easy to write. But you might consider

approaching them as a tour guide or baseball announcer.

The Tour Guide

|

| Gettysburg battlefield (image (c) Emilyk | CC by 3.0) |

The Baseball Announcer

|

| Imagine yourself as an announcer, like Harry Caray, famous American baseball broadcaster (Public domain image modified from the original by Delaywaves.) |

Now envision yourself doing the play-by-play announcing for

a baseball game. At the end of each inning, you announce the score and recap what

happened during that inning (like the chapter summary). Then you might say who’s

coming to bat in the next inning and talk a little about what these players are

facing this inning, based on the team’s history against this particular

opponent, and how the game has progressed so far (like the transition statement).

Finally, you run down the names of the three lead-off batters (like the preview).

Whether visiting a historic site, watching a baseball game,

or trying to follow the argument of a complex research study, guidance is

needed to recall what has been seen or read, how that fits in the bigger

picture, and what is coming up next. Summaries, transition statements, and

previews provide critical continuity in capstone studies.

Summaries, transition statements, and previews provide critical continuity in capstone studies.

Dissertation Editor Tim McIndoo, who joined Walden University in 2007, has more than 30 years of editorial experience in the fields of education, medicine, science and technology, and fiction. When it comes to APA style, he says, "I don't write the rules; I just help users follow them."

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Summaries, transition statements, and previews provide critical continuity in capstone studies.

Dissertation Editor Tim McIndoo, who joined Walden University in 2007, has more than 30 years of editorial experience in the fields of education, medicine, science and technology, and fiction. When it comes to APA style, he says, "I don't write the rules; I just help users follow them."

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

WriteCast Episode 15: What To Do With Negative Feedback on Your Writing

Feeling frustrated, discouraged, or confused about feedback on your writing? Want to know how to handle these feelings in the future? Don't miss our discussion with Dr. Melanie Brown, associate director and manager of writing initiatives at the Walden Writing Center. Dr. Brown also teaches Walden student support courses, and she has a lot of helpful advice for students on what to do with negative faculty feedback.To download the episode to your computer, press the share button on the player above, then press the download button. Visit the Writing Center's WriteCast page for our episode archive and transcripts. Happy listening!

Blog posts mentioned in this episode: "Help Them Help You: Being Receptive to Faculty Feedback"

WriteCast is hosted by writing instructors Nikolas Nadeau and Brittany Kallman Arneson and produced by writing instructor Anne Shiell. Check out the podcast archive for more episodes.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

How to Give Useful Peer Feedback

Throughout this article are 12 "tweetable takeaways." Click on a Twitter icon ( ) to share one of Lydia's peer review tips.

) to share one of Lydia's peer review tips.

Giving and getting peer feedback on drafts can be an incredible tool for improving your writing, but only if that feedback is clear and specific about what to do next. Having someone say, “I liked it!” or “Well done!” can feel good for a moment, but it won’t help anyone improve.

) to share one of Lydia's peer review tips.

) to share one of Lydia's peer review tips. Giving and getting peer feedback on drafts can be an incredible tool for improving your writing, but only if that feedback is clear and specific about what to do next. Having someone say, “I liked it!” or “Well done!” can feel good for a moment, but it won’t help anyone improve.

You also don’t have to “know

everything” to give helpful writing feedback; just be self-aware about your own

reading experience. The whole point of feedback is to just show the author what

a reader will see in a draft.

|

| Is peer review part of your writing process? |

General Strategies

Find out what the author wants, but keep in mind you may see things

the author hasn’t considered yet, too.

Don’t give too much; don’t give too little. Sometimes it is not

helpful to point out every error and make suggestions on every line—this can be

overwhelming. Vague or incomplete feedback can be just as frustrating and can

feel like a waste of time.

Follow the golden rule. Give the kind of feedback that you would

like to get. That is, be respectful, constructive, thorough, and honest.

Trust yourself as a reader. If something is not clear to you, the

author probably needs to make it clearer. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense

because the author hasn’t made sense of it yet.

Content Critique versus Error Correction

You don’t need to be a grammar or APA expert to give worthwhile feedback. Address the big things first! For example, if you are reading over someone’s problem statement, it is probably more important that the author made sure you could understand the point than if he or she used a semicolon correctly. Focus on content and clarity before you

focus on mechanical errors, like typos or missing punctuation. Proofreading

concerns should come last unless they significantly interfere with a reader’s overall

understanding.

Thinking of Things to Say

Keep track of questions that

occur to you as you read. For example: How does this

point relate to the one before? What does this term mean? Is there a missing

word here?

Offer concrete suggestions

whenever you can. For example: This

paragraph might work better at the beginning. I was confused here—maybe a

subheading would make the transition clearer.

Examples of things to focus on in

a content critique:

- Organization (are things in a logical order?)

- Consistency/contradiction (does the author say the same thing throughout or seem to change his or her mind?)

- Focus (can you tell what the main ideas are, or is there a lot of extra information?)

- General clarity (make note of passages that don’t seem to make sense to you, either because the wording is confusing, there is not enough explanation, or you can’t tell how the information fits in to the main idea)

- Point out when authors do

something well, too, and let them know why. For example: The obvious topic sentences really helped me follow your argument. The wording

in this paragraph is clear and easy to understand. Explaining it this way is

much better than in the earlier paragraph—now I know what you mean.

Don’t Get Stuck

If you can’t find something

positive to say about a draft, look at it from another perspective: The wording

is dense and hard for you to understand, but maybe you can really tell how

knowledgeable the author is about the topic. (When people have a lot to say, sometimes

it just takes a few drafts to make sure they say everything in the right

order.)

If you come across something you

just don’t understand, tell the author this, but also say what you think it means—sometimes when an author

hears a reader’s interpretation (or misinterpretation) of an idea, the author

can more easily figure out what to fix.

If you can’t find anything to

critique, focus on making sure the author knows why

what he or she did worked. Don’t just say “This is awesome!” Be specific: “I could

really tell how all the scholarly evidence fit together—the way you explained

things and gave examples was really helpful.”

Interpreting Feedback for Your Own Work

Try not to take it personally—you

are very close to your own writing and may think you have settled on the right

way to do things. What makes sense in your

head may not make sense in someone else’s.

Be grateful! Thoughtful feedback

takes time and mental energy. If someone has a lot of suggestions, don’t think

of it as “tearing your paper apart;” think of how many ways he or she is trying

to make it better.

You don’t have to follow every

suggestion, but keep an open mind. A fresh pair of eyes may catch something you

missed.

Getting #writing feedback: Don't take it personally, be grateful, & stay open-minded.

Giving and getting peer review feedback is an excellent way to develop your skills as a writer. We encourage you to join a writing community and/or find a writing partner to make peer review a regular part of your writing process.

Getting #writing feedback: Don't take it personally, be grateful, & stay open-minded.

Giving and getting peer review feedback is an excellent way to develop your skills as a writer. We encourage you to join a writing community and/or find a writing partner to make peer review a regular part of your writing process.

Practice: Find a draft of something you wrote a while ago. Pick something you haven’t written or read recently so that you have some distance from it. Take 10-15 minutes to read over and make comments on the draft, imagining you are giving feedback to a colleague on his or her work. What kinds of things do you notice? What suggestions for revision can you make?

.png)

Lydia Lunning is one of the editors in the Writing Center who conduct the final form and style review of all of Walden’s dissertations and doctoral studies. She was terrible at revising her own work until she joined a peer tutoring program in college.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Ready, Set, Write! It’s time for #NaNoWriMo and #AcWriMo.

Do you thrive under pressure?

Need to set a few goals for yourself and your writing? Want to challenge

yourself in your writing?

November marks the beginning

of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and Academic Writing Month (AcWriMo).

This is the month for writers and academics across the globe to come together

for accountability and motivation to start that novel they’ve always wanted to

write or to work on an academic writing project. It’s a great chance for

writers to get involved in a goal-oriented and fun writing community!

Have you ever considered jumping on the writing bandwagon? Tobias Ball (Dissertation Editor and Developmental Editing Coordinator), Amber Cook (Manager of Program Outreach and Faculty Support), and Nathan Sacks (Writing Instructor) of our Writing Center staff have participated or are considering participating in NaNoWriMo. Here’s what they have to say:

Why did you choose to participate in AcWriMo and/or NaNoWriMo?

Tobias Ball (Dissertation Editor and Developmental

Editing Coordinator): “I did it

because [a coworker] ...suggested I give it a try. I had an idea for a novel

that I had not yet started, so I went for it.”

Amber Cook (Manager of Program Outreach and Faculty

Support): “I needed a kickstart for a

writing project I’d been dreaming about for a while. I was always overwhelmed

at the idea of committing to such a long-term goal, so having a month-long

challenge made it seem much more doable.”

Nathan Sacks (Writing Instructor): “Any writing practice is good writing practice, and I

look at NaNoWriMo as a chance to work on a completely new project I have never

thought of or worked on before.”

You participated in NaNoWriMo in the past. What were the drawbacks to participating?

Tobias: “There

were no drawbacks. It was fun and I wrote 85,000 words in 4 weeks. It felt good

to start and complete something.”

Amber: “I

got really behind on my Netflix queue. :) [Also] November is a

tough month, with Thanksgiving travel and pre-holiday business, and I lost some

steam at the end last time. I have a desk job, so it was sometimes hard to make

myself spend yet another few hours at a desk for so many days in a row.”

What particular challenges did you experience or do you expect to encounter?

Tobias: “My

regular pattern is to start my day with about an hour of writing. […] I added

some writing time at night.”

Nathan: “If

you can’t write one day because of an emergency or other reason, it may be

harder to get back on the saddle and keep working for the rest of November. [Another

challenge is] running up against the limits of my knowledge and imagination,

which is always when I generate the best stuff.”

What benefit would it be to Walden students to participate in AcWriMo and/or NaNoWriMo?

Amber: “The

short-term nature of the challenge helps keep the end in sight, so it doesn’t

seem as overwhelming as, say, a 12-month project. It also provides a helpful

accountability framework, allowing you to connect with others on the same solitary

journey and reminding you to stay on track with your page count.”

Are YOU up

for the challenge? See PhD2Published's AcWriMo 2014 announcement and the NaNoWriMo official website for more details.

Practice: For the next 10 minutes, think about a writing goal that you have for this month. Then, declare your goal in the comments! Remember to provide feedback to other writers to help them stay motivated and accountable towards their goals.

.png)

Rachel Grammer is a writing instructor and the coordinator of student messaging at the Walden Writing Center. The best writing advice she has received is to turn off the "internal editor" when beginning a paper--a great tip for starting AcWriMo or NaNoWriMo!

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Writing Center Services Announcement from the Director

As many of you have probably heard by now, the Writing

Center and Academic Skills Center have recalibrated their services to better

support student writing at Walden. In short, we are (a) adding doctoral writing workshops for capstone (premise, prospectus, and proposal) writers and

(b) shifting of our paper review service to serve undergraduate, master’s, and

doctoral students in coursework only. This means that by the end of the year our

paper review schedule will no longer accommodate capstone drafts, but all of

our other services (e.g., course visits, developmental editing, Q&A

support, webinars) will continue to support capstone writers.

The rationale

for this change is twofold: We want to (a) reserve skill-building sessions for

those students still in the formative stages of their degrees and (b) create a

scalable service via the workshops to ensure that all students needing

assistance at this stage can be supported (e.g., we can continue to grow our

faculty to accommodate our enrollment).

While this

change may be welcome to some and less so to others, I do want to remind you about all of the services we offer with the following figure.

Walden Writing Center Services

Key:

Available to All Students

Exclusive to Students Working on Their Capstones

Exclusive to Undergraduate Students

Exclusive to All PreProposal Students

* Available via the Walden Writing Center website

** Membership may be requested at editor@waldenu.edu

ǂ 24-48 hours from day of appointment, exclusive to students working on their coursework

Brian Timmerman is the director of the Walden Writing Center and the Academic Skills Center.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

From the Archives: Writing Through Fear

Happy Halloween, readers! Today seems like the perfect day to resurrect Hillary's post on working through writing fear, originaly published in 2013.I suppose fall is the perfect time to discuss fear. The leaves are falling, the nights are getting longer, and the kids are preparing ghoulish costumes and tricks for Halloween.

So here’s my scary story: A few weeks ago, I sat down at my computer to revise an essay draft for an upcoming deadline. This is old hat for me; it’s what I do in my personal life as a creative writer, and it’s what I do in my professional life as a Walden Writing Center instructor. As I was skimming through it, though, a feeling of dread settled in my stomach, I began to sweat, and my pulse raced. I was having full-on panic. About my writing.

This had never happened to me before. Sure, I have been disappointed in my writing, frustrated that I couldn’t get an idea perfectly on paper, but not completely fear-stricken. I Xed out of the Word document and watched Orange Is the New Black on Netflix because I couldn’t look at the essay anymore. My mind was too clouded for anything productive to happen.

The experience got me thinking about the role that fear plays in the writing process. Sometimes fear can be a great motivator. It might make us read many more articles than are truly necessary, just so we feel prepared enough to articulate a concept. It might make us stay up into the wee hours to proofread an assignment. But sometimes fear can lead to paralysis. Perhaps your anxiety doesn’t manifest itself as panic at the computer; it could be that you worry about the assignment many days—or even weeks—before it is due.

Here are some tips to help:

1. Interrogate your fear.

Ask yourself why you are afraid. Is it because you fear failure, success, or judgment? Has it been a while since you’ve written academically, and so this new style of writing is mysterious to you?2. Write through it.

We all know the best way to work through a problem is to confront it. So sit at your desk, look at the screen, and write. You might not even write your assignment at first. Type anything—a reflection on your day, why writing gives you anxiety, your favorite foods. Sitting there and typing will help you become more comfortable with the prospect of more.3. Give it a rest.

This was my approach. After realizing that I was having an adverse reaction, I called it quits for the day, which ultimately helped reset my brain.4. Find comfort in ritual and reward.

Getting comfortable with writing might involve establishing a ritual (a time of day, a place, a song, a warm-up activity, or even food or drink) to get yourself into the writing zone. If you accomplish a goal or write for a set amount of time, reward yourself.5. Remember that knowledge is power.

Sometimes the only way to assuage our fear is to know more. Perhaps you want to learn about the writing process to make it less intimidating. Check out the Writing Center’s website for tips and tutorials that will increase your confidence. You can also always ask your instructor questions about the assignment.6. Break it down.

If you feel overwhelmed about the amount of pages or the vastness of the assignment, break it up into small chunks. For example, write one little section of the paper at a time.7. Buddy up.

Maybe you just need someone with whom to share your fears—and your writing. Ask a classmate to be a study buddy.The writing centers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Richmond, as well as the news site Inside Higher Ed, also have helpful articles on writing anxiety.

Practice: For the next 10 minutes, think about your own writing fears. What writing tasks or assignments make you anxious? How do you, or how will you, work through them? Share your practice in the comments below this post, and don't forget to give feedback to fellow writers.

.png)

Hillary Wentworth is a writing instructor and the coordinator of undergraduate instruction. She has worked in the Walden Writing Center since 2010, and she enjoys roller-skating and solving crossword puzzles.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

.jpg)

2 comments :

Post a Comment