APA Page Numbers Explained

Student

writers often send us questions about page numbers: When do I need to include a

page number in a citation? What if there is no page number? What if there is no

page number and no paragraph number? Can I include a page number with a paraphrase?

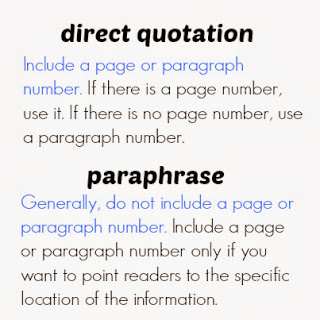

The Shorter Answer

The Longer Answer

When directly quoting a source, you’re using the author’s words,

word order, punctuation, and even mistakes in the same way they appear in the

source. If a reader wants to find that quotation, perhaps to see the context

around the quotation in the original source, he or she is going to want to find

the quotation quickly and will need a page or paragraph number to do so.

When you paraphrase, however, you

are often using information or ideas that appear in more than one place in a

source. Pointing readers to all 21 pages where they can find the information

you paraphrased would be more annoying than helpful. Just imagine if all of

your citations looked like this: (Shiell, 2013, p. 3, 4, 5, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22,

34, 41, 42, 43, 47, 59, 60, 64, 65, 98, 101, 102, 103). However, to direct

readers to the exact location of the information you’re paraphrasing—perhaps a

statistic, for example, or a small portion of a large work—APA suggests

including a page or paragraph number in your citation.

What if the Source Doesn't Have a Page or a Paragraph Number?

Web pages typically do not use

page numbers, so students often mistakenly label a web page as p. 1. Or,

they might print the web page and use the page numbers assigned by their

printer. The trouble with this method is that different printers assign

different numbers to the pages, potentially creating confusion for readers.

If the source doesn’t have a page

number, APA says to use a paragraph number. Many web pages don’t have numbered

paragraphs, though, and can contain numerous paragraphs. If the purpose of

providing a page or paragraph number is to easily direct readers to the

information you used, expecting readers to count each paragraph in the source

until they find para. 103 defeats the point. In such cases, APA says writers

can use a heading or a section description and count the paragraph underneath

it.

Here's an example. Like many

webpages, the CDC

page on Worker Safety During Fire Cleanup page does not have page numbers or numbered paragraphs,

but the information is organized by sections with headings. To cite information

about the primary types of electrical injury, which is located in the first

paragraph after the heading Electrical Hazards, your parenthetical citation

would look like this: (CDC, 2013, “Electrical Hazards,” para. 1).* Readers

familiar with APA will know (or can figure out) that the citation points to the

first paragraph after the Electrical Hazards heading.

*This citation assumes that this

is not the first time you are citing the CDC in your paper. For information on

how to format citations for sources that use an acronym, see this page.

For more detail on these page and

paragraph number rules, see pages 171-172 and 179 in the 6th edition of

the APA manual. Do you have other questions about page and paragraph numbers?

Let us know in the comments!

Other posts you might like:

Demystifying In-Text vs. Parenthetical CitationsAPA Citations: The Method to the Madness

What's the Citation Frequency, Kenneth?

Citing an Author Throughout a Paragraph: Notes on a Tricky APA Shortcut

When to Use an Author Name in the Body of a Sentence and When to Keep It in the Parenthetical Citation

Hiring an Outside Editor

In the Writing Center, we offer a variety of tools and services to assist Walden students. Through a 30-minute one-on-one-review with one of our Writing Instructors, for instance, both undergraduate and graduate students can receive personalized feedback on their writing that they can apply in the revision process. By using the Grammarly website, students can check the originality of their work and identify recurrent patterns of error. Our many webinars offer students tips and guidance on specific writing issues, as does our website.

We offer all of these tools and services free of charge to current Walden students to help them as they develop the skills they need to be effective editors of their own work. Some students, however, want more extensive assistance with grammar, clarity, and formatting than we can provide. Such students may choose to hire a paid, private editor not affiliated with Walden University. Below, I will address some common questions about the use of such outside editors.

|

| Image (c) Nic McPhee |

What services can a private editor provide?

A private academic editor may provide a range of services, from basic proofreading or copyediting (checking grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc.) to more intensive editing to improve flow and clarity. Editing services may or may not include citation and document formatting (some editors assess an additional charge for these services).

When hiring an editor, it is important to clarify the nature and extent of the service that will be provided so that expectations are established. Will the editor only correct elements of the manuscript that are objectively incorrect (e.g., errors of grammar, punctuation, and spelling), or will the editor also make changes to improve the document in more subjective ways, such as by eliminating redundancy, improving clarity, or adjusting awkward phrasing? Will the editor correct in-text citations and the reference list, and does he or she have a strong command of APA style? Will the editor ensure that the document is consistent with the appropriate Walden formatting template?

An editor should not be expected to address issues related to the content or methodology of a study. Although an editor can help students make significant improvements to grammar, style, and formatting, a document that has been professionally edited is still likely to require some additional work on the student’s part.

What services should a private editor not provide?

A private editor should not be hired to write new content or to develop a student’s research or ideas. Such use of an editor constitutes an academic integrity violation. (For Walden’s policy on the use of outside editors, please see this page from the Center for Research Quality; scroll down to the section titled “Editors.”)

How much do private editing services cost?

Costs are highly variable but generally depend on two factors: (a) the length of the work and (b) the service(s) provided. Many editors charge an hourly rate, while others charge by the page. Make sure that you have established clear expectations regarding cost when hiring an editor.

How do I select a private editor?

Because Walden University does not maintain relationships with third-party editors and cannot guarantee their services, we do not offer specific editor recommendations. Peers in your department are often the best sources of referrals to editors who have performed good work in the past. Students can also use the Walden Writing Center Facebook page or eCampus discussion board to discuss their experiences with editors and seek referrals. For more tips on locating an editor, see this Writing Center handout.

Some editors will edit a short excerpt of your work as a sample. Others may offer sample documents on a website to illustrate the work they perform. Review these materials carefully to ensure that the editor’s approach matches your needs.

If you have any questions about the Writing Center’s

free services for students at various stages of the writing process, please

contact writingsupport@waldenu.edu

for a response within 24 hours.

Carey Little Brown has more than a decade of experience as the lead editor of an academic editorial firm. As a dissertation editor in Walden's Writing Center, she helps students master APA style, avoid common grammatical errors, and use concise language to develop compelling written work.

Student Spotlight: Jennifer Sulkowski

This Student Spotlight features Jennifer Sulkowski, who

is pursuing her PhD in Public Health with a focus on community outreach and

education. Fluent in Swahili and interested in the role of literacy and

education on local health in developing countries, Jennifer saw a way to create

social change in Eastern African by writing a book for children that would

reflect their lives and experiences. Her book, A Pony Named Napoleon, was published in July 2013, and all of the

proceeds and royalties go directly to Joy Beginners School in Nairobi.

What inspired you to write A Pony Named Napoleon?

In Michigan, I live and work on a horse farm that is also

home to many abandoned and abused animals, including a zebra (who makes his debut

in the book). I really admire the animals—they’ve been through so much and have

no reason to trust humans or each other, but they do. It is amazing to watch

them play and be free and forget about what once hurt them, so I end up taking

lots of pictures of them playing together in the pastures or enjoying the

comfort and safety of the warm barn at night.

My other home is Kenya, where my lovely Kenyan family

lives and works to keep Joy Beginners School running in Kangemi Slums, which is

outside of Nairobi. My Kenyan family and my students are why I wrote the book. When

I got back from a trip to Kenya this past May, I realized Joy Beginners School

needed help, and I was determined to come up with some sort of way to help the

students. I wasn’t comfortable asking people for money, so I had the idea to

write a book that could raise money for the school, if I found a publisher. I

selected what I thought were the most interesting photos of the farm animals,

and I knitted them together with a fairytale about friendship, acceptance, and

bullying. I was excited about the real pictures because I hoped kids would see

that fairy tales can be real, and I tried to write a story with a universal

message, so that my Kenyan students could relate to it just as well as my little

nephew here in the United States.

Tell us about how the book came to be.

I thought I would write the book and if no publishers

were interested, I would just go to Kinko's and make 330 copies. If nothing

more, the children would have their own makeshift storybook sent to them. But

that's not what happened. An indie publisher, Inkwater Press, was interested in

my book and published A Pony Named Napoleon with some requested revisions.

I thought I would write the book and if no publishers

were interested, I would just go to Kinko's and make 330 copies. If nothing

more, the children would have their own makeshift storybook sent to them. But

that's not what happened. An indie publisher, Inkwater Press, was interested in

my book and published A Pony Named Napoleon with some requested revisions.What is your writing process?

To be honest, my writing process is a bit all over the

place. I wrote A Pony Named Napoleon

in two nights, including the time it took to factor in the revisions requested

by the publisher. I have another children’s book I am hoping to get published

within the next few months. The publisher has approved it, but I have yet to

find an illustrator for all the animals in the story, so if there are any

talented Walden artists out there, I’d love to hear from and collaborate with

you! That book also only took me a night or two to write. However, I have a

young adult novel that I’ve been working on for years! It’s nowhere close to

being done. I do keep various journals and logs and a blog and I have lots of

scraps of paper with notes and ideas that I jot down when I see something

interesting or meet someone interesting, so if I’d just sit down and put

all of those together, my novel might be finished, too!

Do you have a favorite strategy or resource that you use to help strengthen your writing?

The Walden Writing Center! But it’s also important

just to write, and practice. And read, too. I love reading storybooks and old

novels (used bookstores are like Wonderland!) because then I’m reminded about

what’s really possible in writing…which is anything. If you can dream it, you can

write it. Sometimes, you need to get lost in someone else’s writing before

you’re brave and bold enough to create your own.

What aspect of writing do you find the most challenging?

The editing process is incredibly painful for me because I

am always over the word count/page limit. I confuse thoroughness with

redundancy. Peer review is essential for polished writing, but even the most

constructive of criticisms can be tough to take sometimes. I think that’s okay

because it just means that you’ve written what you love (or rather, you love

what you’ve written), but you have to be flexible and be willing to make

changes so that it’s polished and presentable to the rest of the world. Truly,

it’s a sign of respect to your audience, and when I think about it that way,

criticism is easier to take. Sometimes, though, I still have to sleep on it for

a night (or two!) before swallowing my pride and fixing what desperately needs

to be fixed.

How would you compare writing scholarly papers to writing a book for children?

In my experience, both types of writing require you to know

your audience and what you are trying to accomplish with your writing, given

that audience. I think peer review and working with editors are essential for

any type of writing.

There is more freedom in creative writing, especially for

children, because anything is possible, and you don’t have to spend any time

convincing kids of that. That makes for a neat space to tell a story. Scholarly

writing is more rigid, of course, and you usually have to be objective and

follow a specific format. When I was in Boston this past week for Walden’s APHA

professional conference residency, however, I learned that there are different

formats for delivering scientific messages. For example, some presenters told

stories or showed video clips, instead of using PowerPoint slides, and the

audience walked away from those sessions giving rave reviews because they were

effectively different.

Do you have any advice or words of wisdom for fellow students interested in writing for social change?

The biggest lesson I’ve learned at Walden is to “think

outside the box,” especially when you’re trying to make a difference or start

something new.

One of the best lines of advice I’ve ever received was from

a Cornell philosophy professor who always told us to “sin boldly.” He told us

to be bold in our writing and our ideas, even if it meant we’d have to break a

few…or a lot…of rules. It wakes people up and it changes their thinking, which

usually sparks inspiration, and then in this way, you’ve created social change.

Our Goals (and Yours!) for AcWriMo and NaNoWriMo

In the academic community, many celebrate November as Academic Writing Month, commonly referred to as AcWriMo. AcWriMo was inspired by the longer-running National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and is all about dedicating time and energy to your academic writing with set goals that you share and celebrate with other writers and supporters. According to the PhD2Published announcement, AcWriMo has six rules for participating:1. Decide on your goal.

2. Declare it!

3. Draft a strategy.

4. Discuss your progress.

5. Don't slack off.

6. Declare your results.

|

| image (c) PhD2Published.com |

|

| Amber: I'm not doing AcWriMo or NaNoWriMo this year, but I learned some useful writing strategies during my NaNoWriMo experience 2 years ago. |

|

| Anne: This is my first time taking part in AcWriMo. I've been working on an article around the WriteCast podcast, and my goal is to finish that draft. |

|

Kayla: My NaNoWriMo goal is just to make 50,000 words by the end of the month—and to develop a workable plot, which I don’t quite have right now. :)

|

As you progress through AcWriMo and NaNoWriMo, know that we are cheering you on! Here are some of our strategies:

- Setting goals—and publicizing those goals—can be scary. Check out Hillary's tips for overcoming writing fear and anxiety.

- Are you having trouble getting started on your goal? See our suggestions for procrastinators.

- Create a writing calendar for your dissertation, final project, novel, or other writing goal to keep yourself on track.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

No comments :

Post a Comment