Five Ways to Create Flow in Your Writing

At the Writing Center, we often

talk about the flow in writing. While

it’s a small word, flow incorporates

many parts of writing, which can make it difficult to define and complicated to

achieve. Creating flow involves using logical connections between ideas,

strong topic sentences to start paragraphs, transitions to

link sentences, concise wording, and a varied sentence structure.

One commonality between these

parts of writing is that they make the reader’s job easier. And, that’s

essentially what flow is: Techniques and characteristics of good writing that

make the writing easy for the reader to navigate and understand. In this way,

good flow is a lot like a good road trip.

If I was writing a paper about the

advantages of online education, I might first discuss how online education can

be useful to people who are working adults, as well as people who live in rural areas. But what if I then talked about how students are more engaged when

they live on campus?

Wait, what?

Topic sentences

Transitions

Transitions create flow by linking ideas and sentences. Writers can create transitions in a couple of ways: (1) using words like additionally or however to begin sentences and (2) repeating key terms or phrases between sentences. Transitions are like bridges between roads. They help guide the reader between sentences, showing the reader how to easily get from one sentence to the next, just like a bridge can bring you from one side of the road to the other safely and easily.Clear, concise wording.

Clear and concise wording also creates flow. Take this sentence: Online education, which means education in an online format where you are not face-to-face with your teacher or classmates, can help a student become more proficient in their area of expertise or field, which in turn can also help a student show leadership skills and receive a promotion or recognition for his/her good work at their job.

Whew, that’s a long one. Note all the phrases and ideas stacked on top of one another that the reader must navigate. Instead, I could have easily said: Online education helps students become proficient in their field, which can result in recognition for students in the form of a promotion. Much clearer! This sentence has the same meaning as my previous sentence, but is more concise and easier to follow. Using concise and precise wording is like creating a direct route in a road trip. Instead of taking your reader through all the winding back roads and causing car sickness, you’re taking the reader on the most direct route to your ideas.

Varied wording and sentence structure

Avoiding repetition creates flow by getting readers interested in your ideas and in the way you talk about your ideas. Think taking a long road trip through flat, rural countryside. Without variety in scenery, the drive can become boring pretty quickly. Variety in scenery—like variety in sentence structure—makes the journey more interesting.Take these sentences, for example: Online education is beneficial for many students. Online education benefits many students in rural areas. Online education benefits many students working full-time jobs. My sentence structure is the same in each sentence (a simple subject + verb construction), and I repeat the words online education, benefit, and many students. Here’s another version that varies the sentence structure and wording, and thus is more engaging: Online education is beneficial for many students. In particular, students in rural areas and those working full-time jobs can find online education convenient and useful.

As you write, remember to use logical

connections; topic sentences; transitions; clear, concise writing; and varied wording

and sentence structure. If you can master these aspects, then you’re on your

way to creating flow in your writing!

Editor's Note: In 2016, we expanded Beth's discussion of flow in academic writing. Our Instructors and Editors expanded on each one of these strategies in a full-length blog post. So, if you'd like more insight and instruction on any of these five categories, check out our Writing Center Greatest Hits Update: 5 Flow. Follow this link to access the expanded, in-depth discussion on increasing your writing's flow today!

Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Webinar Writing Instruction Beth Oyler writes about literature in her spare time and enjoys contemplating the possibilities writing creates.

What to Expect When You're Expressing: U.S. Academic Writing Norms

You’ve likely noticed that here at Walden, you have

needed to adjust your writing style to meet your assignment requirements and

your instructors’ expectations. Many of the norms of scholarly writing, while

not always simple, are at least likely familiar to you: Students must cite sources in APA style, follow specific formatting

requirements (as modeled in our templates), and maintain scholarly voice. Most of the questions we receive in the

Writing Center relate to such issues.

|

| American schools generally teach Standard American English, a form of English with specific requirements and expectations. |

1. Include an introduction and conclusion.

For course papers, these are typically one paragraph each. Think of these as bookends for your paper: They hold the body of your draft together. For some great information on writing an introduction and conclusion, see our webinar titled “Beginnings and Endings: Introduce and Conclude Your Writing.”2. State the main point of your paper in your introduction.

Readers expect you to tell them right off the bat why you are writing the paper: What are you arguing? Why is your paper topic important? Some writers—particularly those who are less familiar with the U.S. writing tradition—are accustomed to building up to their main point throughout a paper and then ending the paper with their argument. At Walden, however, you are expected to state your main idea right away. This is why thesis statements—sentences that encompass your central argument—belong in your introductory paragraph (typically as the last sentence of the paragraph).3. Use a linear organization.

U.S. scholarly writing favors a linear progression of ideas, which means that each paragraph must clearly follow from the previous paragraph and must also relate to the paper’s central argument (expressed in the thesis statement). Writing an outline is often a helpful way to clarify your organization. For example, say that I’m arguing for the addition of professional development opportunities at a local school. My outline might look like this:

I. Introduction

II. Background

a. Current

professional development offerings

b. Why

current offerings are insufficient

III. Introduction of recommended professional

development opportunities

IV. Benefits to these opportunities

V. Potential challenges to implementing

professional development

VI. Suggestions for overcoming these challenges

VII. Conclusion

An outline like this helps ensure that each new paragraph

follows logically and linearly from the previous paragraph.

4. Demonstrate critical thinking.

Readers of American scholarly writing

expect writers not only to research a topic, but also to make arguments based

on that research. They expect writers to summarize but also to analyze, which

often means that you will need to argue against another scholar’s ideas. This

practice can be intimidating, but just remember that such arguments are

essential to the creation of new knowledge. Our webinar titled “Demonstrating Critical Thinking in WritingAssignments” can help you develop this skill.

5. Analyze your evidence for your reader.

In other words, you’ll want to help your reader interpret the evidence you use and cite. Say that you are using this statistic: “The graduating class of 2012 had a 23% dropout rate, an increase of 5% from the class of 2007 (citation).” Instead of just including that statistic and moving on, take some time to explain to your reader what that information means: “This trend reveals a need for immediate action on the part of administrators, teachers, and parents to encourage high school completion.” It may seem like stating the obvious, but this kind of analysis helps to ensure that you and your reader are on the same page.

What other scholarly writing expectations have you

encountered at Walden, or at your school? Are there others we left out? Let us know in the comments!

We’re always looking for ways to improve our resources. If you're a current international and/or multilingual Walden student, please take our brief survey to help us improve our services for you. The survey link will remain posted here as long as the survey is active. Thank you!

Other posts you might like:

WriteCast Episode 002: Thesis StatementsArgue is Not a Dirty Word: Taking a Stand in your Thesis Statement

You're the Navigator! On Introductory Paragraphs and Topic Sentences

Calling All International and Multilingual Students!

A 20-Minute Exercise in Using Specific Language

Maybe you only have a little time to devote to writing today, or maybe your paper is due this evening and you're wondering what other revisions you can reasonably make before needing to submit your work. Here's a quick exercise you can do in just 20 minutes to strengthen your writing.Step 1:

Use Microsoft Word's "find" feature to find every this and it in your paper. Hold down the CTRL key and the F key at the same time, which will open up a navigation panel or box: |

| In MS Word 2010, this navigation panel opens on the side of the page when you hold down CTRL + F. |

Step 2:

Highlight every This or It that starts a sentence in your paper.TIP: When you use the find feature, Microsoft Word automatically highlights the word you searched for in your text. You want to highlight the search results manually, on top of Word's automatic highlights, as the automatic highlighting will disappear once you close the navigation panel.

Step 3:

Make sure that each highlighted This is followed by a specific noun rather than a verb. If a verb comes directly after This, either replace This with a specific noun or add a specific noun between the This and the verb. For example:

Original: The project involves data collection through an emailed survey. This requires that the participants...

Here's another example:

After Thanksgiving dinner is a natural time to take a nap. This is caused by tryptophan in the turkey.

You, like many readers, may be asking yourself: This what is caused by tryptophan? To make the sentence's meaning clearer, the writer should include a specific noun or phrase after this, like This urge to nap.

TIP: Not sure what specific noun to use? You can often use keywords or phrases from previous sentences. Repeating these words, or forms of the words, can help make connections between your sentences.

Step 4:

Now, review each highlighted instance of it, and replace It with a specific noun.Example:

People in the United States celebrate New Year's Eve each December 31. It typically involves a countdown and a ball drop.

Revision: People in the United States celebrate New Year's Eve each December 31. The holiday typically involves a countdown and a ball drop.

That's it!

Why is using specific language important? You might think that what the this or it refers to is clear--but you're the writer, so of course it's clear to you. An unidentified this or it can be confusing for readers, but using specific language helps readers know exactly what you're talking about.

Give this exercise a try, and let us know what you think in the comments!

Anne Shiell is a writing instructor in the Walden University Writing Center. She also coordinates the center's social media resources.

Anne Shiell is a writing instructor in the Walden University Writing Center. She also coordinates the center's social media resources.

What's the Problem With Passive Voice?

Regular readers of the Walden Writing Center blog will know

that we’ve written about passive voice before. As Rachel pointed out in her blog post, passive voice constructions are grammatically

correct. So why does APA prefer active voice? Why do instructors urge

students to change “a study was conducted” to “I conducted a study?”

Getting an answer can sometime seem as vague as the tasting

notes on a fine bottle of wine. Strunk and White wrote that passive voice is

“less bold” while active voice is more “vigorous” and “direct” (p. 18). But again, students may raise the question: Why is passive voice less bold and

vigorous? And what are the factors that make it so?

But it’s not just a lack of accountability that leads APA

and others to prefer active voice constructions. APA also addresses economy of

expression, reminding writers that “short

words and short sentences are easier to comprehend than are long ones” (p. 67). Because of the

structure of passive voice and the inclusion of an auxiliary verb, passive

voice constructions are almost always longer than active voice ones.

Other posts you might like:

When he's not helping Walden students write to the best of their abilities, Writing Instructor Jonah Charney-Sirott enjoys writing fiction.

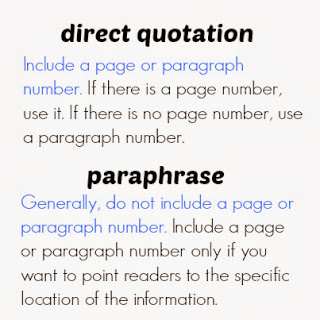

When he's not helping Walden students write to the best of their abilities, Writing Instructor Jonah Charney-Sirott enjoys writing fiction.APA Page Numbers Explained

Student

writers often send us questions about page numbers: When do I need to include a

page number in a citation? What if there is no page number? What if there is no

page number and no paragraph number? Can I include a page number with a paraphrase?

The Shorter Answer

The Longer Answer

When directly quoting a source, you’re using the author’s words,

word order, punctuation, and even mistakes in the same way they appear in the

source. If a reader wants to find that quotation, perhaps to see the context

around the quotation in the original source, he or she is going to want to find

the quotation quickly and will need a page or paragraph number to do so.

When you paraphrase, however, you

are often using information or ideas that appear in more than one place in a

source. Pointing readers to all 21 pages where they can find the information

you paraphrased would be more annoying than helpful. Just imagine if all of

your citations looked like this: (Shiell, 2013, p. 3, 4, 5, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22,

34, 41, 42, 43, 47, 59, 60, 64, 65, 98, 101, 102, 103). However, to direct

readers to the exact location of the information you’re paraphrasing—perhaps a

statistic, for example, or a small portion of a large work—APA suggests

including a page or paragraph number in your citation.

What if the Source Doesn't Have a Page or a Paragraph Number?

Web pages typically do not use

page numbers, so students often mistakenly label a web page as p. 1. Or,

they might print the web page and use the page numbers assigned by their

printer. The trouble with this method is that different printers assign

different numbers to the pages, potentially creating confusion for readers.

If the source doesn’t have a page

number, APA says to use a paragraph number. Many web pages don’t have numbered

paragraphs, though, and can contain numerous paragraphs. If the purpose of

providing a page or paragraph number is to easily direct readers to the

information you used, expecting readers to count each paragraph in the source

until they find para. 103 defeats the point. In such cases, APA says writers

can use a heading or a section description and count the paragraph underneath

it.

Here's an example. Like many

webpages, the CDC

page on Worker Safety During Fire Cleanup page does not have page numbers or numbered paragraphs,

but the information is organized by sections with headings. To cite information

about the primary types of electrical injury, which is located in the first

paragraph after the heading Electrical Hazards, your parenthetical citation

would look like this: (CDC, 2013, “Electrical Hazards,” para. 1).* Readers

familiar with APA will know (or can figure out) that the citation points to the

first paragraph after the Electrical Hazards heading.

*This citation assumes that this

is not the first time you are citing the CDC in your paper. For information on

how to format citations for sources that use an acronym, see this page.

For more detail on these page and

paragraph number rules, see pages 171-172 and 179 in the 6th edition of

the APA manual. Do you have other questions about page and paragraph numbers?

Let us know in the comments!

Other posts you might like:

Demystifying In-Text vs. Parenthetical CitationsAPA Citations: The Method to the Madness

What's the Citation Frequency, Kenneth?

Citing an Author Throughout a Paragraph: Notes on a Tricky APA Shortcut

When to Use an Author Name in the Body of a Sentence and When to Keep It in the Parenthetical Citation

Hiring an Outside Editor

In the Writing Center, we offer a variety of tools and services to assist Walden students. Through a 30-minute one-on-one-review with one of our Writing Instructors, for instance, both undergraduate and graduate students can receive personalized feedback on their writing that they can apply in the revision process. By using the Grammarly website, students can check the originality of their work and identify recurrent patterns of error. Our many webinars offer students tips and guidance on specific writing issues, as does our website.

We offer all of these tools and services free of charge to current Walden students to help them as they develop the skills they need to be effective editors of their own work. Some students, however, want more extensive assistance with grammar, clarity, and formatting than we can provide. Such students may choose to hire a paid, private editor not affiliated with Walden University. Below, I will address some common questions about the use of such outside editors.

|

| Image (c) Nic McPhee |

What services can a private editor provide?

A private academic editor may provide a range of services, from basic proofreading or copyediting (checking grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc.) to more intensive editing to improve flow and clarity. Editing services may or may not include citation and document formatting (some editors assess an additional charge for these services).

When hiring an editor, it is important to clarify the nature and extent of the service that will be provided so that expectations are established. Will the editor only correct elements of the manuscript that are objectively incorrect (e.g., errors of grammar, punctuation, and spelling), or will the editor also make changes to improve the document in more subjective ways, such as by eliminating redundancy, improving clarity, or adjusting awkward phrasing? Will the editor correct in-text citations and the reference list, and does he or she have a strong command of APA style? Will the editor ensure that the document is consistent with the appropriate Walden formatting template?

An editor should not be expected to address issues related to the content or methodology of a study. Although an editor can help students make significant improvements to grammar, style, and formatting, a document that has been professionally edited is still likely to require some additional work on the student’s part.

What services should a private editor not provide?

A private editor should not be hired to write new content or to develop a student’s research or ideas. Such use of an editor constitutes an academic integrity violation. (For Walden’s policy on the use of outside editors, please see this page from the Center for Research Quality; scroll down to the section titled “Editors.”)

How much do private editing services cost?

Costs are highly variable but generally depend on two factors: (a) the length of the work and (b) the service(s) provided. Many editors charge an hourly rate, while others charge by the page. Make sure that you have established clear expectations regarding cost when hiring an editor.

How do I select a private editor?

Because Walden University does not maintain relationships with third-party editors and cannot guarantee their services, we do not offer specific editor recommendations. Peers in your department are often the best sources of referrals to editors who have performed good work in the past. Students can also use the Walden Writing Center Facebook page or eCampus discussion board to discuss their experiences with editors and seek referrals. For more tips on locating an editor, see this Writing Center handout.

Some editors will edit a short excerpt of your work as a sample. Others may offer sample documents on a website to illustrate the work they perform. Review these materials carefully to ensure that the editor’s approach matches your needs.

If you have any questions about the Writing Center’s

free services for students at various stages of the writing process, please

contact writingsupport@waldenu.edu

for a response within 24 hours.

Carey Little Brown has more than a decade of experience as the lead editor of an academic editorial firm. As a dissertation editor in Walden's Writing Center, she helps students master APA style, avoid common grammatical errors, and use concise language to develop compelling written work.

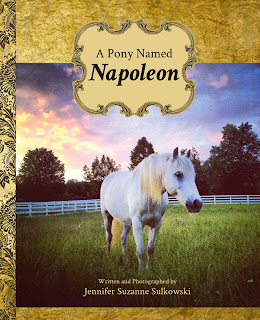

Student Spotlight: Jennifer Sulkowski

This Student Spotlight features Jennifer Sulkowski, who

is pursuing her PhD in Public Health with a focus on community outreach and

education. Fluent in Swahili and interested in the role of literacy and

education on local health in developing countries, Jennifer saw a way to create

social change in Eastern African by writing a book for children that would

reflect their lives and experiences. Her book, A Pony Named Napoleon, was published in July 2013, and all of the

proceeds and royalties go directly to Joy Beginners School in Nairobi.

What inspired you to write A Pony Named Napoleon?

In Michigan, I live and work on a horse farm that is also

home to many abandoned and abused animals, including a zebra (who makes his debut

in the book). I really admire the animals—they’ve been through so much and have

no reason to trust humans or each other, but they do. It is amazing to watch

them play and be free and forget about what once hurt them, so I end up taking

lots of pictures of them playing together in the pastures or enjoying the

comfort and safety of the warm barn at night.

My other home is Kenya, where my lovely Kenyan family

lives and works to keep Joy Beginners School running in Kangemi Slums, which is

outside of Nairobi. My Kenyan family and my students are why I wrote the book. When

I got back from a trip to Kenya this past May, I realized Joy Beginners School

needed help, and I was determined to come up with some sort of way to help the

students. I wasn’t comfortable asking people for money, so I had the idea to

write a book that could raise money for the school, if I found a publisher. I

selected what I thought were the most interesting photos of the farm animals,

and I knitted them together with a fairytale about friendship, acceptance, and

bullying. I was excited about the real pictures because I hoped kids would see

that fairy tales can be real, and I tried to write a story with a universal

message, so that my Kenyan students could relate to it just as well as my little

nephew here in the United States.

Tell us about how the book came to be.

I thought I would write the book and if no publishers

were interested, I would just go to Kinko's and make 330 copies. If nothing

more, the children would have their own makeshift storybook sent to them. But

that's not what happened. An indie publisher, Inkwater Press, was interested in

my book and published A Pony Named Napoleon with some requested revisions.

I thought I would write the book and if no publishers

were interested, I would just go to Kinko's and make 330 copies. If nothing

more, the children would have their own makeshift storybook sent to them. But

that's not what happened. An indie publisher, Inkwater Press, was interested in

my book and published A Pony Named Napoleon with some requested revisions.What is your writing process?

To be honest, my writing process is a bit all over the

place. I wrote A Pony Named Napoleon

in two nights, including the time it took to factor in the revisions requested

by the publisher. I have another children’s book I am hoping to get published

within the next few months. The publisher has approved it, but I have yet to

find an illustrator for all the animals in the story, so if there are any

talented Walden artists out there, I’d love to hear from and collaborate with

you! That book also only took me a night or two to write. However, I have a

young adult novel that I’ve been working on for years! It’s nowhere close to

being done. I do keep various journals and logs and a blog and I have lots of

scraps of paper with notes and ideas that I jot down when I see something

interesting or meet someone interesting, so if I’d just sit down and put

all of those together, my novel might be finished, too!

Do you have a favorite strategy or resource that you use to help strengthen your writing?

The Walden Writing Center! But it’s also important

just to write, and practice. And read, too. I love reading storybooks and old

novels (used bookstores are like Wonderland!) because then I’m reminded about

what’s really possible in writing…which is anything. If you can dream it, you can

write it. Sometimes, you need to get lost in someone else’s writing before

you’re brave and bold enough to create your own.

What aspect of writing do you find the most challenging?

The editing process is incredibly painful for me because I

am always over the word count/page limit. I confuse thoroughness with

redundancy. Peer review is essential for polished writing, but even the most

constructive of criticisms can be tough to take sometimes. I think that’s okay

because it just means that you’ve written what you love (or rather, you love

what you’ve written), but you have to be flexible and be willing to make

changes so that it’s polished and presentable to the rest of the world. Truly,

it’s a sign of respect to your audience, and when I think about it that way,

criticism is easier to take. Sometimes, though, I still have to sleep on it for

a night (or two!) before swallowing my pride and fixing what desperately needs

to be fixed.

How would you compare writing scholarly papers to writing a book for children?

In my experience, both types of writing require you to know

your audience and what you are trying to accomplish with your writing, given

that audience. I think peer review and working with editors are essential for

any type of writing.

There is more freedom in creative writing, especially for

children, because anything is possible, and you don’t have to spend any time

convincing kids of that. That makes for a neat space to tell a story. Scholarly

writing is more rigid, of course, and you usually have to be objective and

follow a specific format. When I was in Boston this past week for Walden’s APHA

professional conference residency, however, I learned that there are different

formats for delivering scientific messages. For example, some presenters told

stories or showed video clips, instead of using PowerPoint slides, and the

audience walked away from those sessions giving rave reviews because they were

effectively different.

Do you have any advice or words of wisdom for fellow students interested in writing for social change?

The biggest lesson I’ve learned at Walden is to “think

outside the box,” especially when you’re trying to make a difference or start

something new.

One of the best lines of advice I’ve ever received was from

a Cornell philosophy professor who always told us to “sin boldly.” He told us

to be bold in our writing and our ideas, even if it meant we’d have to break a

few…or a lot…of rules. It wakes people up and it changes their thinking, which

usually sparks inspiration, and then in this way, you’ve created social change.

Our Goals (and Yours!) for AcWriMo and NaNoWriMo

In the academic community, many celebrate November as Academic Writing Month, commonly referred to as AcWriMo. AcWriMo was inspired by the longer-running National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and is all about dedicating time and energy to your academic writing with set goals that you share and celebrate with other writers and supporters. According to the PhD2Published announcement, AcWriMo has six rules for participating:1. Decide on your goal.

2. Declare it!

3. Draft a strategy.

4. Discuss your progress.

5. Don't slack off.

6. Declare your results.

|

| image (c) PhD2Published.com |

|

| Amber: I'm not doing AcWriMo or NaNoWriMo this year, but I learned some useful writing strategies during my NaNoWriMo experience 2 years ago. |

|

| Anne: This is my first time taking part in AcWriMo. I've been working on an article around the WriteCast podcast, and my goal is to finish that draft. |

|

Kayla: My NaNoWriMo goal is just to make 50,000 words by the end of the month—and to develop a workable plot, which I don’t quite have right now. :)

|

As you progress through AcWriMo and NaNoWriMo, know that we are cheering you on! Here are some of our strategies:

- Setting goals—and publicizing those goals—can be scary. Check out Hillary's tips for overcoming writing fear and anxiety.

- Are you having trouble getting started on your goal? See our suggestions for procrastinators.

- Create a writing calendar for your dissertation, final project, novel, or other writing goal to keep yourself on track.

Writing Through Fear

I suppose

fall is the perfect time to discuss fear. The leaves are falling, the nights

are getting longer, and the kids are preparing ghoulish costumes and tricks for

Halloween.

So here’s my scary story: A few weeks ago, I sat down at my computer to revise an essay draft for an upcoming deadline. This is old hat for me; it’s what I do in my personal life as a creative writer, and it’s what I do in my professional life as a Walden Writing Center instructor. As I was skimming through it, though, a feeling of dread settled in my stomach, I began to sweat, and my pulse raced. I was having full-on panic. About my writing.

3. Give it a rest. This was my approach. After realizing that I was having an adverse reaction, I called it quits for the day, which ultimately helped reset my brain.

4. Find comfort in ritual and reward. Getting comfortable with writing might involve establishing a ritual (a time of day, a place, a song, a warm-up activity, or even food or drink) to get yourself into the writing zone. If you accomplish a goal or write for a set amount of time, reward yourself.

5. Remember that knowledge is power. Sometimes the only way to assuage our fear is to know more. Perhaps you want to learn about the writing process to make it less intimidating. Check out the Writing Center’s website for tips and tutorials that will increase your confidence. You can also always ask your instructor questions about the assignment.

6. Break it down. If you feel overwhelmed about the amount of pages or the vastness of the assignment, break it up into small chunks. For example, write one little section of the paper at a time.

Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Undergraduate Writing Initiatives Hillary Wentworth works and writes from her home in Portland, Maine. When she's not at a computer, she likes to read, roller skate, and travel to new places.

So here’s my scary story: A few weeks ago, I sat down at my computer to revise an essay draft for an upcoming deadline. This is old hat for me; it’s what I do in my personal life as a creative writer, and it’s what I do in my professional life as a Walden Writing Center instructor. As I was skimming through it, though, a feeling of dread settled in my stomach, I began to sweat, and my pulse raced. I was having full-on panic. About my writing.

This had

never happened to me before. Sure, I have been disappointed in my writing,

frustrated that I couldn’t get an idea perfectly on paper, but not completely

fear-stricken. I Xed out of the Word document and watched Orange Is the New Black on Netflix because I couldn’t look at the essay

anymore. My mind was too clouded for anything productive to happen.

The

experience got me thinking about the role that fear plays in the writing

process. Sometimes fear can be a great motivator. It might make us read many

more articles than are truly necessary, just so we feel prepared enough to articulate

a concept. It might make us stay up into the wee hours to proofread an

assignment. But sometimes fear can lead to paralysis. Perhaps your anxiety

doesn’t manifest itself as panic at the computer; it could be that you worry

about the assignment many days—or even weeks—before it is due.

Here are some tips to help:

1. Interrogate your fear. Ask yourself why you are afraid. Is it because you fear failure, success, or judgment? Has it been a while since you’ve written academically, and so this new style of writing is mysterious to you?

2. Write through it. We all know the best way to

work through a problem is to confront it. So sit at your desk, look at the

screen, and write. You might not even write your assignment at first. Type

anything—a reflection on your day, why writing gives you anxiety, your favorite

foods. Sitting there and typing will help you become more comfortable with the

prospect of more.

3. Give it a rest. This was my approach. After realizing that I was having an adverse reaction, I called it quits for the day, which ultimately helped reset my brain.

4. Find comfort in ritual and reward. Getting comfortable with writing might involve establishing a ritual (a time of day, a place, a song, a warm-up activity, or even food or drink) to get yourself into the writing zone. If you accomplish a goal or write for a set amount of time, reward yourself.

5. Remember that knowledge is power. Sometimes the only way to assuage our fear is to know more. Perhaps you want to learn about the writing process to make it less intimidating. Check out the Writing Center’s website for tips and tutorials that will increase your confidence. You can also always ask your instructor questions about the assignment.

6. Break it down. If you feel overwhelmed about the amount of pages or the vastness of the assignment, break it up into small chunks. For example, write one little section of the paper at a time.

7. Buddy up. Maybe you just need someone with

whom to share your fears—and your writing. Ask a classmate to be a study buddy

or join an eCampus group.

The writing centers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and University of Richmond, as well as the news site Inside Higher Ed, also have helpful articles on writing anxiety.

Other posts you might like:

Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Undergraduate Writing Initiatives Hillary Wentworth works and writes from her home in Portland, Maine. When she's not at a computer, she likes to read, roller skate, and travel to new places.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

32 comments :

Post a Comment