Mapping Your Mind With Bubbl.us

I am not a visual

learner. That’s what I told myself, anyway, when studying for college exams with

a friend and attempting to make sense of the crazy bubbles that comprised his

history notes. He tried to convince me that the mess of scribbles he called a

“mind map” was an excellent way of note-taking, but I stubbornly stuck to my

chronological, college-ruled list.

A mind map begins with a

key concept or idea written in the center of a piece of paper or electronic

space, and the idea is usually enclosed in a bubble. Related ideas, also in

bubbles, branch out from that center idea. As the writer

adds more and more ideas, making additional branches and sub-branches, the

writer can also use lines or arrows to connect ideas. I realized the beauty of

those interconnected bubbles years later when, older and wiser, I tried mind

mapping for a graduate school assignment. If I had used a mind map back in

college and been able to better visualize the relationships between the events,

people, and social movements that I was studying, I might have scored better on

that history exam.

To create a mind map, you

can use good old pen and paper or a free electronic mapping tool like Bubbl.us, which allows you to color code

your ideas and easily add, delete, and rearrange bubbles. I’ll use screenshots

from Bubbl.us here to show how a mind map

begins and develops.

So, let’s say you’re

writing a paper on bullying in U.S. high schools. This main topic goes in a bubble

in the center of the page:

Next, start branching off

of that central bubble with related ideas. What comes to mind when you think

about bullying in U.S. high schools? What do you know from course work, preliminary

research, or personal experience? For example, the topic might make you think

about prevention programs, effects of bullying, and different types of

bullying. These subtopics can each go in a bubble that branches off from the

main bubble, like this:

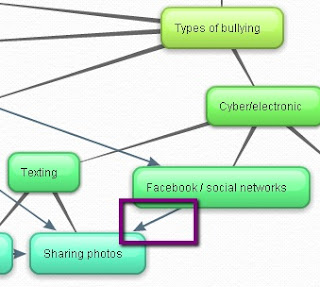

Then, keep branching off

of these bubbles with additional ideas, categories, subcategories—anything you

can think of that’s related, including words, phrases, facts, quotations,

questions, examples, and sources. Pretty soon, your mind map will start looking

like this:

As your mind map grows,

use arrows to connect your ideas. You might first think about sharing photos as

a type of bullying done through text messaging, for example, but then realize

that bullying through Facebook can also involve sharing photos. Even though the

“Sharing photos” bubble branches off of the “Texting” bubble, you can link

“Facebook/social networks” to “Sharing photos” with an arrow.

Creating a mind map can

be a freeing way to capture and connect all of your ideas on a topic. Even if

you’re more comfortable with a traditional outline, you might find—as I

did—that using a different form of brainstorming and note-taking can help expand

your thinking and see connections you might have otherwise missed. Also, looking

at the overall structure of your mind map can help you determine if you need to

broaden or narrow your topic to match the scope of your assignment.

Next time you need to

choose a paper topic, take notes, or beat a writer’s block, try this exercise:

- Get out a piece of paper or sign up for Bubbl.us (you can save up to three mind maps with a free account).

- Put your main idea in a bubble at the center of the page or space.

- Spend 10 minutes building your mind map, creating additional bubbles and sub-bubbles that branch off of your main idea.

- Pause, and look at your whole map. Draw lines or arrows to connect related ideas.

Here are a couple tips to keep in mind:

- Use words and phrases, rather than full sentences, in your bubbles.

- Don’t worry about your map looking professional—it’s okay to go a little wild, and it’s okay if no one else understands how to read your map. Your map only needs to make sense to you.

- Don’t limit yourself! The more bubbles, the better. Getting your ideas down on paper (or a screen) can spark others. Afterward, you can always delete bubbles that do not belong.

Mind mapping is not just

for academic writing. It can be a helpful tool in the workplace, too. The Wall Street Journal recently published

an

article on how one financial advisory firm is using mind mapping to help

clients negotiate financial planning.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A former teacher of college

composition courses, Writing Instructor Anne Shiell is a self-described punctuation geek.

Writing for Change on Earth Day (and Every Day)

As

a high school student in the early 1990s, I was a typical Birkenstock-wearing,

granola-crunching tree hugger. I listened to the Indigo Girls, Pearl Jam, and

R.E.M. I followed a vegetarian diet. And I mostly didn’t bother with make-up.

At the time I thought I was cool, taking a stand against all that was mainstream,

but in hindsight I can see that I was actually trendy in most of my choices:

what to wear, what to eat, whom to emulate. One way in which I was not like

most of my peers, however, was in my strong sense of activism. I wasn’t much

for standing on picket lines or making speeches—I was too much an introvert to

be comfortable in those arenas—but I believed strongly in the power of the

written word to make things happen.

When

my passion was stirred—as it was the time my hometown decided to build a golf

course on a remnant of land I thought should be a nature preserve—I acted in

the form of editorials to the local newspaper, which I wrote without much

guidance but with plenty of heart, agonizing over every line until I’d said

exactly what I wanted to say. And while I didn’t necessarily always achieve my

goals—the golf course, for example, won in the end—my letters, amateur though

they were, initiated conversations in my community that wouldn’t have happened

otherwise. Conversations about sustainable choices. The best use of limited

resources. The inherent value of natural spaces.

When

my passion was stirred—as it was the time my hometown decided to build a golf

course on a remnant of land I thought should be a nature preserve—I acted in

the form of editorials to the local newspaper, which I wrote without much

guidance but with plenty of heart, agonizing over every line until I’d said

exactly what I wanted to say. And while I didn’t necessarily always achieve my

goals—the golf course, for example, won in the end—my letters, amateur though

they were, initiated conversations in my community that wouldn’t have happened

otherwise. Conversations about sustainable choices. The best use of limited

resources. The inherent value of natural spaces.

A lot has changed over the past

20 years (including, incidentally, my choice of footwear), but I still have

tremendous faith in the written word as a catalyst for all kinds of change:

environmental, political, personal, and social. And I’m not alone. For many

organizations committed to change, writing is essential to achieving results. In

honor of Earth Day, I want to highlight one such organization: 350.org. Cofounded by author Bill McKibben in 2008, 350.org

is a growing global movement committed to solving the climate crisis by

“creating an equitable global climate treaty that lowers carbon dioxide below

350 parts per million.” For those of you not familiar with the numbers, 350

parts per million (ppm) is the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that many

scientists, including Dr. James Hansen of NASA, consider the safe upper limit

for humanity; according to 350.org, we’re currently at 392 ppm, well past the

threshold of safety.

Part of 350.org’s strategy of creative

activism involves engaging individuals in online campaigns and grassroots

organizing efforts that include writing letters and op eds to initiate

conversations about climate change in communities around the world. To

encourage participation, 350.org provides supporters with templates, sample

letters, and tips on writing an effective op ed, among other resources. Tools

such as these make it easier and less intimidating to engage on a more active

level in environmental and social movements, even for those without experience

in writing for a cause. Just as importantly, they take the emphasis off the

overwhelming nature of the challenge and focus attention on smaller steps that

are both possible and powerful.

For more inspiration and

suggestions on writing for change, I recommend Mary Pipher’s (2007) Writing

to Change the World and The Freedom Writers’ (1999) The

Freedom Writers Diary.

Happy Earth Day, everyone!

Dissertation editor Jen Johnson "has a particular interest in helping students craft well-written doctoral research, from the sentence level up."

We Haiku. Do You?

By Writing Center Staff

In honor of National Poetry Month, the Walden Writing Center

is running a haiku contest. Full details and rules are here:

So . . . what’s a haiku? According to Merriam-Webster’s Online

Dictionary, it is “an unrhymed verse form of

Japanese origin having three lines

containing usually five, seven, and five

syllables respectively.” Because they are so short, haiku usually

present just one moment in time. They also tend to focus on the natural world.

Here’s an example:

Toward those short trees

We saw a hawk descending

On a day in spring

– Masaoka Shiki

Tips:

- Say it out loud. I know we give this advice for academic writing, but it works for poetry as well. Haiku are focused on sounds and syllables, so put your ear to the test.

- Think small to capture the essence of an experience.

- Use imagery. Let the reader see that experience (like the trees and the hawk in the poem above).

Post your haiku on our Facebook page

or Tweet @WUWritingCenter by

April 29th. We will announce a winner on May 1 and feature that

winner on our website. The prize is sort of like a “get out of jail free card”:

one appointment to use when the tutoring schedule is

full.

We look forward to reading your entries. Happy Poetry

Month!

Putting It All Together: Thesis + Synthesis

By Matt Smith, Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Graduate Writing Initiatives

You’ve probably heard the term thesis before from a writing teacher, and we comment on this often in the Writing Center as well because almost any scholarly document—from a discussion post to a dissertation—must have some kind of central, guiding purpose. You may not, however, have heard much about synthesis, or you may have only heard it mentioned vaguely. Synthesis doesn’t get quite as much attention as a thesis does, which is a shame: it’s really just as important. Without it, your document would lack cohesion, and your reader would have to work much harder to understand the overall meaning of your work.

If you look at the etymological roots of the word synthesis, you’ll find that it basically means “to put together.” Pair it with analysis, which means “to take apart,” and you’ve got two of the most fundamental functions of academic work—taking information apart and putting it back together to make something new. In your time at Walden, you’ve probably developed strong analytical skills, and you’ve practiced demonstrating this analysis in your discussion posts and course papers. You’ve probably been synthesizing too, but synthesis is often less explicit than analysis because it mainly involves the connections between ideas rather than the ideas themselves. This can make it difficult to identify and even more difficult to add more of when your peers, Writing Center instructors, or faculty members suggest that a spot in your text doesn’t have enough of it.

You’ve probably heard the term thesis before from a writing teacher, and we comment on this often in the Writing Center as well because almost any scholarly document—from a discussion post to a dissertation—must have some kind of central, guiding purpose. You may not, however, have heard much about synthesis, or you may have only heard it mentioned vaguely. Synthesis doesn’t get quite as much attention as a thesis does, which is a shame: it’s really just as important. Without it, your document would lack cohesion, and your reader would have to work much harder to understand the overall meaning of your work.

If you look at the etymological roots of the word synthesis, you’ll find that it basically means “to put together.” Pair it with analysis, which means “to take apart,” and you’ve got two of the most fundamental functions of academic work—taking information apart and putting it back together to make something new. In your time at Walden, you’ve probably developed strong analytical skills, and you’ve practiced demonstrating this analysis in your discussion posts and course papers. You’ve probably been synthesizing too, but synthesis is often less explicit than analysis because it mainly involves the connections between ideas rather than the ideas themselves. This can make it difficult to identify and even more difficult to add more of when your peers, Writing Center instructors, or faculty members suggest that a spot in your text doesn’t have enough of it.

Put another way, text without synthesis is like bricks without mortar: you have the essential substance, but there’s nothing to hold it together, rendering the whole thing formless and unable to support the argumentative weight of your thesis.

|

Text without synthesis (above) and with synthesis (below).

|

If you think

you need to add synthesis in your writing, or if someone else has suggested

this, you may be wondering how, exactly, to do so. This can be tricky, because

synthesis can look different from one situation to another. To effectively

detect synthesis (or a lack thereof), you’ll need to think about the function

of a sentence or paragraph rather than its structure or content—or, in other

words, you’ll need to determine what the

sentence accomplishes rather than how

it looks.

If you’re looking at a portion of text that doesn’t quite fit with the rest, ask yourself these questions as you read:

If you’re looking at a portion of text that doesn’t quite fit with the rest, ask yourself these questions as you read:

- Does this text logically follow from the sentence or paragraph that comes before it?

- Does it contribute to and support my overall argument?

- Are its connections to the other ideas in my text clear?

Arter (2008) pointed out that, since the

early twentieth century, strain theories have been used to describe crime and

delinquency. In his study, Arter used general strain theory as a theoretical

framework to test the application of the theory on a highly stressed adult

population and to determine how officers in different policing assignments cope

with stress and deviance. Arter also utilized phenomenological methodology to

mitigate one of the criticisms of the general strain theory, the argument that

individuals experiencing the same or similar circumstances often react

differently to deviance or delinquency.

Notice that

this paragraph contains useful evidence and analysis, and, if I asked myself

the above questions with regards to this text, my answer to the first one would

have to be “yes.” However, I’d answer “no” to the second and third questions,

because there’s nothing here that explicitly shows the reader how Arter’s work

relates to the overall thesis or to the other ideas in the paper. This is a

pretty strong indication, then, that this paragraph would benefit from some

additional synthesis. I might add a sentence like this to clarify these

connections:

Arter (2008) pointed out that, since the

early twentieth century, strain theories have been used to describe crime and

delinquency. In his study, Arter used

general strain theory as a theoretical framework to test the application of the

theory on a highly stressed adult population and to determine how officers in

different policing assignments cope with stress and deviance. Arter also utilized phenomenological methodology

to mitigate one of the criticisms of the general strain theory, the argument

that individuals experiencing the same or similar circumstances often react

differently to deviance or delinquency. The

benefits of this phenomenological approach make Arter’s study a more effective

model for my own research than Adams’s (2008) or Ilford’s (2010).

Note that this is just one way to synthesize this material; another writer would handle it differently, and in other situations this approach—adding a concluding sentence—may not be appropriate. Sometimes, for instance, it may make more sense to devote an entire paragraph to a piece of synthesis, showing how a major component of your text relates to other major components (this usually occurs in longer documents like dissertations or doctoral studies); at other times, you might synthesize within another sentence that focuses on your topic, your evidence, or your analysis. Whatever the situation, you’ll want to focus on the function of a given sentence or paragraph and its connections to the rest of your text to identify synthesis or places in need of it.

Matt Smith, who earned a BA in English from Saint John's University and an MFA in writing from Hamline University, says, "It's at once paradoxical and commonsensical, but it's true: you get better at writing by writing."

April Showers Bring . . . New Titles: A Message From Leadership

Greetings,

Waldenites!

Recently you

may have noticed a change on the Writing Center website and

in our e-mail signatures. This is not

some ploy to confuse you all. Rather, we

have undergone a restructuring within the center, and part of this restructuring

has presented the Writing Center staff with new (and well-deserved!) titles. No

longer will you see writing tutors. Instead, we are writing instructors.

Why the switch? The Writing Center staff is a very

knowledgeable and busy group of people, and the term tutor does not accurately reflect everything we do, which is a lot:

conduct paper reviews, host webinars, create website content, answer questions

about writing, post to social media, design tutorials and course guides, write

blog posts, and teach at residencies. At

the heart of the Center is writing instruction, so the term

instructor better indicates our job

on a day-to-day basis. I hope this title

shift will better represent our work and services to people outside of our

center. It also appeases us wordsmiths. (What can I say? We are a bunch of word

nerds and grammar geeks, so having a title that did not define what we do was

just preposterous!)

What will change for you, the student? Nothing! We will still be offering all of our same services, including paper

reviews. We will just be updating our

signatures and language on the website and scheduling system to reflect these new

titles.

We are the

same folks who have always been here for you, just with shiny new titles. Stop

by our About Us page to

learn more about each of the instructors.

We look

forward to continuing to work with you!

Amy Kubista

Manager of

Writing Instructional Services

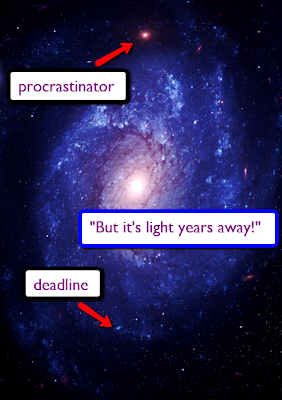

The Procrastinator’s Guide to the Galaxy

In academic life, we find ourselves writing on a strict deadline

for a myriad of reasons: a last-minute assignment, hectic schedule, or (in my

case) a love of procrastination. Whatever puts your finger to keyboard in a

manic fashion, writing with minimal time requires an entirely different

approach. Over years of term papers, applications, and a thesis, I have honed

this art of writing on a deadline. Here are some tips for cranking out an A+

writing assignment last minute.

Claim your writing space.

Having a space that works for your productivity is key. Some prefer the clamor of coffee mugs at Starbucks, others the solitude of their basement. Stake out your claim and plug in your laptop. Also inform your roommate/partner/child of your impending writing blitz.Acquire appropriate snacks.

As much as stress conjures an insatiable craving for Taco Bell, heavy fast food isn’t the answer. Studies have shown blueberries, dark chocolate, avocados, eggs, and whole grains make the best brain food.Assess the situation and set goals.

Figure out exactly what you need to write, how long you have to write it, and how much sleep you need to function. Sometimes, it helps to write an “I’ll do this before 11 p.m., this before 12 a.m., etc.” list to keep yourself organized into the wee hours of insanity and caffeine crashes.Outline.

Nothing helps a frenzied mind more than structure and direction. Outline everything while your brain is fresh.Focus on structure.

If you need to prioritize, keep your writing organized and your language simple. An organized paragraph goes farther than flowery language.Take mini breaks.

A 5-10-minute chat with a friend, brief snack session, or blog check can only help to refresh your brain. Just make sure the mini break doesn’t turn into an hour-long Facebook detour and marathon of Law and Order: SVU.Revise.

When you’re finished, resist the temptation to Blackboard and crash. Read over the assignment at least once before submission. Early risers may choose to sleep and then proofread as soon as they get up. I would not know.Reward yourself.

Writing on a deadline is far more stressful than writing normally, so you should reward yourself for surviving the endeavor. In my experience, a meal out or a massage does the trick. And possibly plan your time better for the next assignment—unless, of course, you enjoy the adrenaline rush. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In her role as a writing instructor, Julia Cox enjoys helping students "discover their own writing process and how to make writing meaningful, rather than just another chore." She lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

3 comments :

Post a Comment