I suppose

fall is the perfect time to discuss fear. The leaves are falling, the nights

are getting longer, and the kids are preparing ghoulish costumes and tricks for

Halloween.

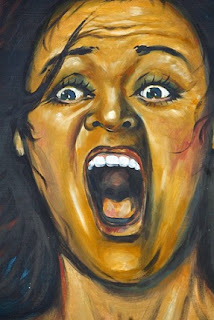

So here’s my scary story: A few weeks ago, I sat down at my computer to revise an essay draft for an upcoming deadline. This is old hat for me; it’s what I do in my personal life as a creative writer, and it’s what I do in my professional life as a Walden Writing Center instructor. As I was skimming through it, though, a feeling of dread settled in my stomach, I began to sweat, and my pulse raced. I was having full-on panic. About my writing.

3. Give it a rest. This was my approach. After realizing that I was having an adverse reaction, I called it quits for the day, which ultimately helped reset my brain.

4. Find comfort in ritual and reward. Getting comfortable with writing might involve establishing a ritual (a time of day, a place, a song, a warm-up activity, or even food or drink) to get yourself into the writing zone. If you accomplish a goal or write for a set amount of time, reward yourself.

5. Remember that knowledge is power. Sometimes the only way to assuage our fear is to know more. Perhaps you want to learn about the writing process to make it less intimidating. Check out the Writing Center’s website for tips and tutorials that will increase your confidence. You can also always ask your instructor questions about the assignment.

6. Break it down. If you feel overwhelmed about the amount of pages or the vastness of the assignment, break it up into small chunks. For example, write one little section of the paper at a time.

Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Undergraduate Writing Initiatives Hillary Wentworth works and writes from her home in Portland, Maine. When she's not at a computer, she likes to read, roller skate, and travel to new places.

So here’s my scary story: A few weeks ago, I sat down at my computer to revise an essay draft for an upcoming deadline. This is old hat for me; it’s what I do in my personal life as a creative writer, and it’s what I do in my professional life as a Walden Writing Center instructor. As I was skimming through it, though, a feeling of dread settled in my stomach, I began to sweat, and my pulse raced. I was having full-on panic. About my writing.

This had

never happened to me before. Sure, I have been disappointed in my writing,

frustrated that I couldn’t get an idea perfectly on paper, but not completely

fear-stricken. I Xed out of the Word document and watched Orange Is the New Black on Netflix because I couldn’t look at the essay

anymore. My mind was too clouded for anything productive to happen.

The

experience got me thinking about the role that fear plays in the writing

process. Sometimes fear can be a great motivator. It might make us read many

more articles than are truly necessary, just so we feel prepared enough to articulate

a concept. It might make us stay up into the wee hours to proofread an

assignment. But sometimes fear can lead to paralysis. Perhaps your anxiety

doesn’t manifest itself as panic at the computer; it could be that you worry

about the assignment many days—or even weeks—before it is due.

Here are some tips to help:

1. Interrogate your fear. Ask yourself why you are afraid. Is it because you fear failure, success, or judgment? Has it been a while since you’ve written academically, and so this new style of writing is mysterious to you?

2. Write through it. We all know the best way to

work through a problem is to confront it. So sit at your desk, look at the

screen, and write. You might not even write your assignment at first. Type

anything—a reflection on your day, why writing gives you anxiety, your favorite

foods. Sitting there and typing will help you become more comfortable with the

prospect of more.

3. Give it a rest. This was my approach. After realizing that I was having an adverse reaction, I called it quits for the day, which ultimately helped reset my brain.

4. Find comfort in ritual and reward. Getting comfortable with writing might involve establishing a ritual (a time of day, a place, a song, a warm-up activity, or even food or drink) to get yourself into the writing zone. If you accomplish a goal or write for a set amount of time, reward yourself.

5. Remember that knowledge is power. Sometimes the only way to assuage our fear is to know more. Perhaps you want to learn about the writing process to make it less intimidating. Check out the Writing Center’s website for tips and tutorials that will increase your confidence. You can also always ask your instructor questions about the assignment.

6. Break it down. If you feel overwhelmed about the amount of pages or the vastness of the assignment, break it up into small chunks. For example, write one little section of the paper at a time.

7. Buddy up. Maybe you just need someone with

whom to share your fears—and your writing. Ask a classmate to be a study buddy

or join an eCampus group.

The writing centers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and University of Richmond, as well as the news site Inside Higher Ed, also have helpful articles on writing anxiety.

Other posts you might like:

Writing Instructor and Coordinator of Undergraduate Writing Initiatives Hillary Wentworth works and writes from her home in Portland, Maine. When she's not at a computer, she likes to read, roller skate, and travel to new places.